Geology is too important to be left to geologists, says Patrick Corbett ahead of Geopoetry 2020

We’re used to hearing that the planet is under threat, but what does that really mean? The planet itself is surely safe – what is under threat are species and people. We can try our best to control geological processes, but – as we are constantly reminded by events like flooding, earthquakes, tsunamis and sea level change – it seems the geology is always in charge.

So why don’t people appreciate this more? It may be that they don’t read our textbooks, and I doubt this will change. The answer is perhaps that we need more use of the poetry of geoscience – or geopoetry. Not weighty technical details of lithology, stratigraphy, taxonomy, sedimentology, geomechanics, geochemistry - but fears of the underworld, love of birds, care for the planet. Poems ‘make one feel, but also understand. They inspire and upset, they provoke and reflect’ (Parkinson, 2019).

Young people are increasingly engaging with poetry - on the internet they, and not the publishers, are in control of their footprint. Geologists must enter this space - for fear of missing out.

Below: A present day geologist getting down to a detailed examination of a specimen in the field

A history of geology in poetry

“Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear/and the rocks melt wi’ the sun”

“Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear/and the rocks melt wi’ the sun”

-Robert Burns, "A Red Red Rose" (1794)

Geology and geologists have featured in poems for centuries - these lines by Burns might be taken as among the first mentions of rocks in a poem. Seas do indeed run dry and rocks do melt – but only through geological processes. As Colin Will suggested at an event celebrating geopoetry at the Geological Society in 2011, Burns may have written these lines after his meeting with James Hutton.

William Wordsworth’s poem Excursion (1814) contains perhaps the first reference to the geologist in the lines “He who with pocket-hammer smites the edge/of luckless rock or prominent stone, disguised/ In weather stains or crusted o’er by Nature/ The substance classes by some barbarous name/ and thinks himself enriched,/Wealthier and doubtless wiser than before. Barbara Maddox has suggested the barbarous words are a reference to the Germanic language of geology - schist, gneiss, greywacke. Clearly the geologist was entering the conscientious – perhaps a result of the formation of the Geological Society of London in 1807.

Touring Scotland in 1818, the English Romantic poet John Keats passed Alisa Craig, and wrote in his "Sonnet to Aisla Rock" "Hearken thy craggy ocean pyramid!" He couldn’t have known that the rock represented the core of an ancient volcanic system but he still surmised “Drown’d wast thou till an earthquake made the steep/ Another cannot wake thy giant size”.

Poetry and geology combined

The late 19th century saw a flowering of geopoetry at a time when debates between scientists and artists were commonplace (McKimm, 2011). Since then, poetry and the geological sciences have drifted apart – is it time for geopoetry reconvergence?

There is plenty of scope for poets to engage with geology and current global concerns - Michael McKimm, for example, has engaged with climate change and geoscience in his collection 'Fossil Sunshine. In 'Oil Field', he writes,

'...the beam pump's/gentle purr, like an antique Singer threaded/through with jet, working with a rhythm/you would never think so peaceful or so clean.'

McKimm also addresses carbon capture and storage in a poem of that title:

'silica bound/by intense warming, Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum/boundary of an epoch, carbon dump.' The 'PETM' clearly captures poetic attention, even if the widely used scientific mnemonic is rather unexciting!

Sometimes geology is used as a metaphor - one would perhaps exclude such cases as geopoetry. The Rocks of Bawn from the traditional Irish folk song of that name ("and you will never be able for to plough the Rocks of Bawn") have not been identified; the reference is perhaps a poetic one to the stony ground that can never be ploughed.

In Simon Armitage’s “Stanza Stones” (2013), hikers in the Pennines encounter poems literally carved into outcrops, “…walling you/into these moments/into this anti-garden/of gritstone and peat”. There must be scope for other such projects in places of geological significance, giving hikers a chance to read the stones and take a moment to reflect on the spirit of place.

Communicating geoscience

There are few poems for young people that capture geological poems - and songs with geological lyrics ('when the levee breaks') are rare. The Hugh Miller Creative Writing competition (that we are promoting at Geopoetry 2020) seeks to redress this with rewarding new contributions by young poets. Dinosaurs are one of the most popular geological subjects among children. Barbara Cumbers’ poem “Dinosaur Footprints, IoW” stirs the memories of fossil hunting as a child: “Dinosaurs had walked here once – huge feet/left prints on ripples in a delta’s swamp” . Scottish poet, Edwin Morgan gives a voice to the Archaeopteryx: “I am only half out of this rock of scales./ What good is armour when you want to fly?” It would be appropriate in 2020, 100 years since Morgan’s birth, to give voice to more dinosaurs.

Sam Illingworth's Poetry of Science blog includes many new poems on geoscientific topics. A recent publication (Illingworth, 2019) describes the lives of scientists who were also poets (none of these are geoscientists). Illingworth points out that poets such as Keats were worried that science would “steal away some of the magic from the world”. Keats was concerned about “negative capability” – the uncertainty that appears to increase the more we know. In this, sense geoscience seems to introduce “negative capability” in human appreciation of natural processes.

Geological Inspiration

Left: Cludders Rocks (Image: Mike Stephenson)

Left: Cludders Rocks (Image: Mike Stephenson)

The UK is home to many famous sites that have inspired geologists to write poetry. An example is Colin Will’s Siccar Point: “places where other boots/sought purchase and a brief stance/on this steep green staircase”. Mike Stephenson visits the Yorkshire sites that inspired Ted Hughes (Stephenson, 2019) and the experience of poetry and geology draws out insights into the meaning of some of his poems. Hughes’s take on Millstone Grit is perhaps captured in the lines “… big animal of rock” and “…kneeling in the cemetery of its ancestors”.

Geological heritage and human experience in response to these natural “cathedrals” will continue to provide a rich seam to be mined. Hugh MacDiarmid’s “On a Raised Beach” contains the lines “What happens to us /Is irrelevant to the world’s geology/But what happens to the world’s geology /Is not irrelevant to us./We must reconcile ourselves to the stones/Not the stones to us.”. These suggest that poets continue to be inspired by geological phenomena. Sarah Acton notes in reflections of our totemic Jurassic Coast (Acton 2017): “this cliff is lone ranger, our frontier messenger/carrying DNA for earth revival, should/the next extinction allow survival”

Celebrations of geologists in poetry

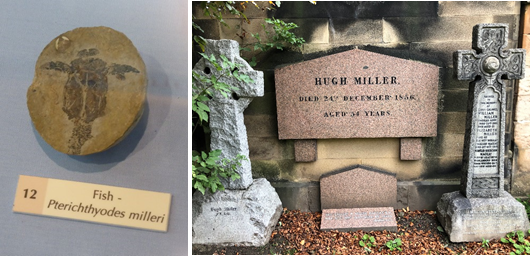

Right: Pterichthyodes milleri (photo byMichael Davenport) and Hugh Miller’s gravestone in Grange Graveyard, Edinburgh

Right: Pterichthyodes milleri (photo byMichael Davenport) and Hugh Miller’s gravestone in Grange Graveyard, Edinburgh

Michael Davenport recently drew attention to a poem that he had written about the famous 19th Century Geologist Hugh Miller, Pterichthyodes milleri: “He splits a nodule to reveal the first example/of a ‘winged-fish’ from the Old Red Sandstone.” This poem received 3rd prize in the 2016 Hugh Miller Writing Competition, a competition that will be featured at Geopoetry 2020, and illustrates the continuing inspiration for modern geologists.

Yvonne Reddick is on the trail of a French geologist in her poem “Cristaux de Roche”; “Relics of her grandfather Resteau,/the one with the alpenstock/and geologist’s hammer./ My thoughts trail him/

Haiku are usually celebrations of a moment, a passing bird, a season – so perhaps this is a poetic form that will have to be adapted for geologists’ celebratory moments. Gary Snyder wrote this on climbing the Sierra Mountains again “Range after range of mountains/Year after year after year./I am still in love.” You can imagine many a field geologists returning to their beloved field areas expressing the same emotions: “Outcrop after outcrop of Book Cliffs/sequence after sequence after sequence/ I am still in love” might equally claim Haiku’s “maximum effect for minimum means” (Washington, 2003).

A geopoetic future

Discussion between scientists and artists took centre stage at a 2011 Geological Society event, ‘Poetry and Geology: A Celebration.’ On 1 October this year, the Society, in conjunction with the Central Scotland Group, is currently organising ‘Geopoetry 2020’ with the Scottish Poetry Library and the Edinburgh Geological Society.

Geopoetry 2020 is an opportunity for all those interested in geology and poetry to get together to discuss the interplay between the two. Coming before COP26 in Glasgow (assuming both are able to go ahead in these uncertain times), it would be nice to see submissions to the former that could also be presented as part of the latter, to enable reflection on geologists’ feelings for our planet.

The Scottish Centre for Geopoetics was set up by followers in the footsteps of the Scottish poet Kenneth White and where there is perhaps only a gradational boundary between geopoetry and geopoetics (Corbett, 2020), Geopoetry 2020 is an opportunity for all those interested in geology and poetry to work together to intercalate more geoscience into poetics.

Wake up, fellow geologists – the wider public is worried about the planet. We must learn to communicate better in their language, not just in ours.

Author

Patrick Corbett is Heriot-Watt University Poet for 2020 and welcomes geopoetic contributions ([email protected]).

References

Armitage, 2013, Stanza Stones, Gomer Press, 110p.

Acton, 2017, Jurassic Coast Poems, Black Ven Press,

Corbett, 2020, Geopoetry and Geopoetics, The Edinburgh Geologist, Spring

Cumbers, 2019, http://www.indigodreams.co.uk/barbara-cumbers/4590943382

Davenport, 2016 https://www.scottishgeology.com/wp-content/uploads/HughMillerWritingComp2016-PoetryJoint3rdPlace-MichaelDavenport.pdf

Ellis, (1954 reprinted 2018), The Pebbles on the Beach, Faber & Faber, 217p

Illingworth, 2019, A sonnet to science, Manchester University Press, 212p

McKimm, 2011, https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Geoscientist/Archive/June-2011/Fugitive-poems-connected-with-natural-history-and-physical-science-Collected-by-the-late-C-G-B-Daubeny-1869

McKimm, 2013, Fossil Sunshine, Worple Press, 27p.

Morgan, 1982, “The Archaeopteryx’s Song”, from Poems of Thirty Years, Carcanet New Press

Parkinson, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/dec/06/verse-soul-saver-poetry-hannah-jane-parkinson?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

Reddick, 2017, Translating Mountains, Seren, 28p

Stephenson, 2019, https://britgeopeople.blogspot.com/2019/12/poetic-reflections-on-geological-walk.html?m=1

Washington, 2003, Haiku, Everyman 256p.

Will, 2006, Sushi & Chips, Calder Wood Press