Camilla Gibbons* describes progress since the damaging earthquakes that hit the New Zealand city in 2010-11.

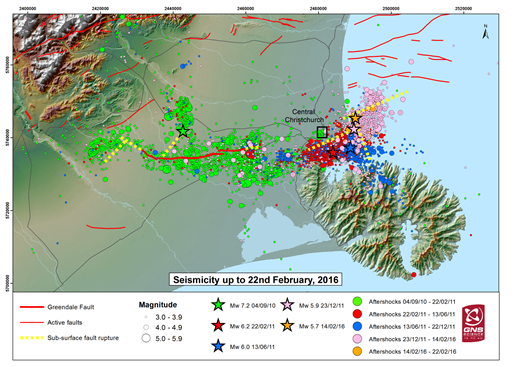

June 13 this year marks the fifth anniversary of the last of the ‘big’ earthquakes that hit Christchurch in 2010 - 2011. The ‘Canterbury Earthquake Sequence’ as it is properly referred to, comprised three major quakes, with over 10,000 aftershocks (which continue, albeit less frequently, today). The latest shake causing damage occurred on Valentine’s Day this year.

Canterbury Plains

Picture: Seismicity in Christchurch region, up to 22 February 2016.

Picture: Seismicity in Christchurch region, up to 22 February 2016.

Christchurch, on the east coast of New Zealand's South Island is located on the Canterbury Plains, an area 8000km2 of glacio-fluvial gravels overlain with deep alluvial deposits laid down over the last 3Ma. The basal Greywacke bedrock is several hundred metres below surface at the city centre, but the southern suburbs of Christchurch lie on the eroded flanks of the extinct basaltic Lyttelton Volcano.

In February 2011, the city was hit by a M6.3 earthquake with a recorded maximum Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA) of 2.2g. The city had experienced a large earthquake only five months previously in September 2010 with the M7.1 Darfield quake just 50km west of the city centre; however that caused significantly less devastation than the February 2011 quake.

New Zealand declared a National State of Emergency and Civil Defence, along with local and international USAR task force teams, spent many days on a big rescue and then recovery effort. All agencies involved in the recovery effort worked very hard for many months; however in June 2011, the city was hit again by another M6.3 quake centered just a few kilometres to the east of the city centre. The June quake had a greater impact on cliff collapse and rockfall than previous quakes, due to its location and previous damage to the rock mass.

This article follows on from my feature in Geoscientist 22.8 (September 2012) and therefore I will not repeat much of the detail about the work undertaken in the early days after the quake. Go to the online version of this piece for a direct hotlink to my original article.

Organisations

I have spent the last five years working on the after-effects of the earthquakes. Many different organisations have been involved in the recovery of the Greater Christchurch Area:

- CCC - Christchurch City Council

- CERA - the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority, the New Zealand Central Government agency that was set up to manage the Recovery.

- EQC - the Earthquake Commission - the body operating what is essentially a compulsory insurance scheme managed via levies on every insurance policy bought. EQC specialises in natural disaster events, and was set up by the new Zealand central government after World War 2)

- All the private insurance companies

- GNS – Geological and Nuclear Sciences, the Crown Research Institute: essentially the New Zealand equivalent of the British Geological Survey

Earthquakes and other natural disasters drop out of the mainstream news a matter of days after the last survivor is found; but in reality it takes many years for a city or region to recover. Recovery from the Christchurch quakes has been affected by a combination of continuing large aftershocks and new earthquakes, leaving a sense of three steps forward two steps back, or snakes and ladders, in addition to local and national politics, (although these have generally been more help than hindrance) and frictions between insurance companies and the EQC.

Earthquakes and other natural disasters drop out of the mainstream news a matter of days after the last survivor is found; but in reality it takes many years for a city or region to recover. Recovery from the Christchurch quakes has been affected by a combination of continuing large aftershocks and new earthquakes, leaving a sense of three steps forward two steps back, or snakes and ladders, in addition to local and national politics, (although these have generally been more help than hindrance) and frictions between insurance companies and the EQC.

Picture: Rockfall Hazard Mitigation

I am aiming to explore these topics within this article as I have had first-hand experience over the past five years or so of working alongside the city council, CERA, and policy makers for the Central Government, trying to control recovery; all while focusing on my technical work to manage the geotechnical hazards affecting the contractors undertaking work on site.

CERA

In parallel to the work undertaken by the City Council on rockfall remediaton, the central government created the Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority (CERA). CERA was established in late March 2011 as the agency responsible for leading and coordinating the recovery of Christchurch. The agency had a planned life of five years. CERA worked under The Canterbury Earthquake Recovery (CER) Act 2011, which contained particular legislative powers to enable an effective, timely and coordinated rebuild-and-recovery effort. CERA's role (see

www.cera.govt.nz), was to:

- Provide leadership and coordination for the ongoing recovery effort.

- Focus on economic recovery, restoring local communities and making sure the right structures are in place for recovery.

- Enable an effective and timely recovery.

- Work closely with Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (see Footnote), Christchurch City Council, Selwyn District Council, Waimakariri District Council and Environment Canterbury – collectively referred to as the 'strategic partners' – and engage with local communities of greater Christchurch, the private sector and the business sector.

- Keep people and communities informed.

- Administer the CER Act.

Picture: Using a helicopter and monsoon bucket to remove loose debris at the cliff edge

Picture: Using a helicopter and monsoon bucket to remove loose debris at the cliff edge

During its initial establishment, while the country was still in a state of emergency, CERA worked closely with Civil Defence and various early recovery organisations. CERA had been specifically established after the initial emergency response phase was in progress, and its role from the outset was recovery.

Due to the disruption visited upon all ‘normal’ authorities, such as councils, CERA initially took control of most early recovery and, over time and as recovery progressed, its role changed and it gradually handed back control of various aspects of recovery to the agencies, organisations and councils that were managing the day-to-day work before the earthquakes occurred (or were established to undertake the role in the long term).

As I write this now (March 2016), CERA still exists in reality, but its role is rapidly reducing and large portions of the organisation are being transferred to other central or local government departments. The work is still being undertaken and the people doing many of those jobs are still required; but those people are finding that they now report to a different section of the government as former CERA responsibilities are transferred to ‘business as usual’ sections of government. Eventually, CERA as an entity will cease to exist.

Port Hills Residential Red Zone

From a geotechnical perspective, the key role CERA took early on was to ‘zone’ the residential parts of the city as ‘red’ or ‘green’, on the basis of risk from geohazards (primarily liquefaction, lateral spreading, rockfall, cliff collapse and landslides). The level of acceptance of risk was determined based on the risk to life from the rockfall and cliff collapses in the Port Hills, and the likely level of future disruption from liquefaction and lateral spreading hazards on flat land. The identified risk levels or potential for future land damage delineated the red and green zones, respectively.

My first involvement with CERA was in the Port Hills zoning decisions, where the key hazards were rockfall, cliff collapse and landslides. The aim of the zoning was to ultimately ‘red-zone’ those parts of the hills that, due to unacceptably high geotechnical risks (primarily rockfall and cliff collapse) were unsafe to be occupied by residential properties or commercial premises in the long term.

Picture: Emergency Demolition of a cliff-top property following storm damage

Picture: Emergency Demolition of a cliff-top property following storm damage

The zoning was very complex and went through several iterations before the final version was released. The decisions relied on two key sources of information, in addition to field observations. First was a life-safety risk model ultimately produced by GNS. The model’s inputs comprised mapping of the majority of the boulders that fell during the earthquakes, in association with many 2D rockfall risk models along observed and anticipated trajectories. Due to the vast dataset of over 8000 mapped boulders, the modelling replicated the observed run-out distances and bounce heights with a reasonably high level of accuracy.

The second piece of information was a 3D rockfall model across the same Port Hills area, undertaken by a private contractor with technical support from experts in Switzerland and Italy. The two models were commissioned separately: one for the City Council and one for CERA. When the two were compared, we found a good level of agreement between them, with only a few parts of the Port Hills where they disagreed - and these were generally areas with intricate and complex geomorphology and/or geology.

With the rockfall models confirmed, GNS calculated the risk in terms of the Annual Individual Fatality Risk (AIFR) from the probability (likelihood) that a particular person will be killed by rockfall in any year at their place of residence. Risk maps were produced, shading areas within an order of magnitude to create five risk categories ranging from >10-2 to <10-5. In line with international best practice on exposure to risks, the Council and CERA adopted the stance that a risk greater than 10-4 was unacceptable and all properties at unacceptable risk were red-zoned.

Red-zoned residential properties received an offer from the Crown (via the NZ Central Government acting as the Crown’s agent) with three basic options: the Crown would buy the house and the land, or just the land with the insurer dealing with the building demolition and removal, or the resident could choose to retain ownership of the property, knowing that they may not be able to re-build on it.

The intention of this policy was to provide an efficient way to remove affected people from the hazard. This sounds relatively straightforward; however an added level of complexity was introduced by the existence of EQC, who insure land in addition to property and contents. For all insurance claims made after the earthquakes, an EQC claim is also made - and EQC covers the first portion of any claim. Anything over and above this reverts to the private insurance company. For many people, this meant dealing with (at least) EQC, their private insurance company, and a range of local and central government agencies.

My work

Picture: Peacocks Gallop, Summer June 2011

Picture: Peacocks Gallop, Summer June 2011

The initial work largely comprised emergency hazard-reduction, reducing the risk of boulder-roll to residential properties and infrastructure. The situation was unprecedented worldwide, with the volume of rockfall, the unusual seismic situation, so many large aftershocks and new earthquakes. We worked very closely with GNS, undertaking rockfall modelling and risk assessments of all the properties in the Port Hills area.

The Council was eagerly spending money on this emergency work in the first year or so after the earthquakes; however as a sense of normality gradually returned, urgency reduced and with a tightening up of the budgeting controls (or rather implementing budget controls) within the Council came the requirement to start to ‘follow the rules again’. The project manager within the Council started to require proposals and cost estimates, justification for cost over-runs and very much the ‘normal process’ that one would expect; but it took a good 18 months from the end of the State of Emergency for the ‘normal’ processes to start to return.

Since ‘normality’ returned, several rockfall remediation projects have taken place around the city; but the main project I have been involved with is assisting CERA with the demolition of residential properties within the Port Hills Red Zone. Several hundred property owners accepted the Crown’s offer, and CERA then became the owner of many damaged and half collapsed residential and commercial properties requiring demolition.

Picture: Peacocks Gallop, Sumner February 2016

Picture: Peacocks Gallop, Sumner February 2016

All these properties were in high hazard locations, with some in ‘very high risk’ areas, such as teetering on the edge of 80m high cliffs! Over the last four years we have developed many procedures to manage the risk successfully. We are currently around 80% of the way through completing these demolitions. Demolishing buildings in geotechnically unstable areas has called for a very high level of collaboration between contractors, structural and geotechnical engineers, engineering geologists as well as the CERA team.

At all times, the key consideration was the impact that our work had on the wider community. All sites have a ‘no-go’ portion (based on the GNS risk modelling) in which no people are allowed, either in a machine or on foot. At times these zones encompassed half of a property and many properties enjoyed no vehicular access, so innovative solutions were called for. One contractor converted three excavators to be fully remote controlled. This maybe a common thing for the mining industry, but had not previously been used on a demolition site at the top of a cliff with ongoing aftershocks. (I still find it a little disconcerting when the empty digger starts its own engine and tracks itself across the site!)

On another site we had a 250-tonne tracked crane, set up on the top of a cliff with a clam shell attachment that was able to access several properties on very steep terrain on the slopes below. At times on this site the contractor had a five-tonne excavator suspended from the crane, working on the demolition with enough weight on the ground to maintain traction but attached to the crane for safety. We also used more traditional methods - such as helicopters with monsoon buckets.

Once all properties are demolished, the sites will be covered in topsoil and planted with native, low-maintenance plants. As yet, this is an interim measure until the government determines what will be done with the land long term.

Key feature

The establishment of CERA has widely been viewed within the engineering community as a key feature in the recovery effort. The inevitable element of bureaucracy aside, the response has been impressive and Christchurch is certainly well aware that the rest of the world has been watching.

New Zealand lies on the boundary of the Australian and Pacific tectonic plates, and although Christchurch was not the location of the expected earthquake, when the next ‘big one’ does happen, we have developed a system that works. Improvements can and will be made, but ‘disaster resilience’ is now a recognised requirement. Many of the large government agencies such as the Transport Agency, major city councils etc. now employ disaster resilience managers. The New Zealand building code has been updated following the earthquakes and Wellington City Council (where the ‘next big one’ was, and still is expected) has reviewed many of its high-rise buildings. Many landlords have been issued with notices to fix and improve the structural integrity of some structures to bring them up to standard and reduce damage in a future event.

Hindsight is always a great thing, but the key here is to put our learning into practice to improve planning and preparedness for future events, both in New Zealand and around the world.

*Camilla Gibbons CGeol is Associate - Ground Engineering, Infrastructure Services, Aurecon. She can be contacted via email: [email protected]

Footnote

- Ngāi Tahu, is the main Māori iwi (tribe) of the southern region of New Zealand, and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu is its tribal authority.