The Society’s appeal to conserve and digitise the Louis Agassiz fossil fish portfolio has raised over £10,000. Caroline Lam and Michael McKimm report on a remarkable story...

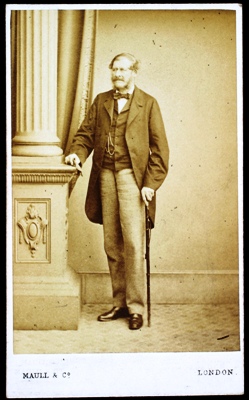

As all avid Geoscientist readers will know, in 2011 (Geoscientist 21.07 August) the Society’s Library and Archive launched a fundraising project to conserve and digitise one of its most important collections – the fossil fish portfolio of the Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz (1807–1873, left). Thanks to the generosity of Fellows and Friends of the Society, as well as many members of the public, by the end of 2012 the appeal has raised over £10,000.

As all avid Geoscientist readers will know, in 2011 (Geoscientist 21.07 August) the Society’s Library and Archive launched a fundraising project to conserve and digitise one of its most important collections – the fossil fish portfolio of the Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz (1807–1873, left). Thanks to the generosity of Fellows and Friends of the Society, as well as many members of the public, by the end of 2012 the appeal has raised over £10,000.

The Society’s collection comprises more than 2000 watercolours and drawings of fossil fish specimens taken from private and public collections around Europe in the 1830s–40s. In recent months, Society archivist Caroline Lam has been collaborating with curators and volunteers at the Natural History Museum to match up our drawings with some of the original specimens, now held in row upon row of metal cabinets in the Department of Palaeontology on Cromwell Road.

In these labyrinthine rooms, Caroline and Senior Library Assistant Michael McKimm were treated to a rare glimpse of these important fossils, ranging from metre-long sharks to boxes crammed with tiny teeth. The chance to compare the original specimens with the drawings has created the opportunity to gain a further understanding about the circumstances in which Agassiz’s seminal texts Recherches sur les Poissons Fossiles (1833-1843) and its follow-up work Monographie des Poissons Fossiles du Vieux Grès Rouge (1844-1845) were created.

WOLLASTON

George Bellas Greenough, in his Presidential address of 21 February 1834, announced that the Wollaston Fund [totalling £32 10s 4d] for that year was to be awarded to “Mr Agassiz of Neuchâtel, in promotion of his work on the ‘General History of Fossil Fishes’.

As well as placing his confidence in Agassiz’s qualifications and competency to complete the important geological work, Greenough publicised the Swiss naturalist’s request for more specimens: “I cannot better close the announcement of a testimony of approbation which I trust will be gratifying to his feelings, than by requesting the Fellows of the Geological Society to aid the progress of this important work, by giving or lending to its author any drawings and specimens of fossil fishes which they may either possess or obtain.”

As well as placing his confidence in Agassiz’s qualifications and competency to complete the important geological work, Greenough publicised the Swiss naturalist’s request for more specimens: “I cannot better close the announcement of a testimony of approbation which I trust will be gratifying to his feelings, than by requesting the Fellows of the Geological Society to aid the progress of this important work, by giving or lending to its author any drawings and specimens of fossil fishes which they may either possess or obtain.”

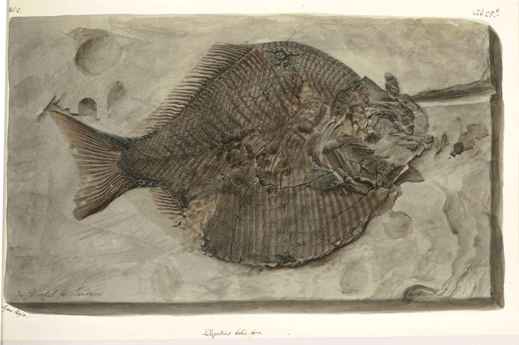

Later in 1834, the Society laid aside a room in its apartments (then at Somerset House) for Agassiz’s principal artist, the Austrian-born Joseph Dinkel (c.1806-1891), to copy the specimens that were sent. Dinkel initially split his time between the Society and the British Museum, drawing specimens such as the Lower Jurassic fish Dapedius colei Agassiz.

For the next decade, Agassiz continued to travel around the palaeontological collections of Britain and Europe seeking out new specimens for his work. Those that were not sent to the holding centre of the Society or his publishing base at Neuchâtel, Switzerland, were drawn in situ by one of Agassiz’s commissioned artists. Wealthy collectors such as Lord William Willoughby Cole (1807-1886, right above), later the Earl of Enniskillen, and Sir Philip de Malpas Grey Egerton (1806-1881 left, below) offered to defray Agassiz’s costs by having specimens from their fossil cabinets drawn by Dinkel at their own expense – the drawings becoming their property, once Agassiz had had them copied onto lithographic stones.

A large proportion of the surviving specimens at the NHM that tally with the Agassiz drawings come from the collections of Enniskillen and Egerton, which the Museum acquired in 1882. The two men, who were lifelong friends and Fellows of the Society, had been inspired to collect fossil fish after becoming acquainted with Agassiz during a trip to Neuchâtel around 1830. Although each man kept his own, distinct fossil cabinet, they would share acquisitions - frequently tossing a coin to see who would get which half of a prized specimen.

A large proportion of the surviving specimens at the NHM that tally with the Agassiz drawings come from the collections of Enniskillen and Egerton, which the Museum acquired in 1882. The two men, who were lifelong friends and Fellows of the Society, had been inspired to collect fossil fish after becoming acquainted with Agassiz during a trip to Neuchâtel around 1830. Although each man kept his own, distinct fossil cabinet, they would share acquisitions - frequently tossing a coin to see who would get which half of a prized specimen.

ACQUISITION

From the beginning of the project, Agassiz had suffered acute financial problems, principally due to the expense of employing a number of full-time artists and lithographers to complete his various works and enterprises. Having already been forced to sell his entire natural history collection to the Neuchâtel district authorities, by the late 1830s the only things of value Agassiz had left were the original drawings of the fossil fish.

Egerton had at first offered the drawings to the British Museum on Agassiz’s behalf, but when this was unsuccessful, he persuaded his wealthy elder brother Lord Francis Egerton (1800-1857), later the Earl of Ellesmere, to purchase the lot for £500, on the understanding that once Agassiz had made use of them, they would then be donated to the Geological Society. This first batch of around 450 sheets of drawings arrived in 1843. In 1858 Agassiz gave the Society a further 568 sheets of unpublished drawings to join the others, and finally in 1876 the Earl of Enniskillen presented the 135 sheets of drawings made by Dinkel and others at his and Egerton’s expense to complete the collection.

DRAWING vs FOSSIL

A number of clear differences emerge between the drawings and the fossils as they are now. Slavish copying, or what would today be referred to as photo-realism, was not the aim of the illustrative work. Rather the intention was to show each fossil fish from a scientific, structural point of view. Frequent handling has taken its toll on some specimens such as the Dapedius colei Agassiz (right). Since Dinkel drew the original specimen in the mid 1830s (left), the delicate and fragile scales around the eye as well as the pectoral fin have been damaged or worn away. Fortunately the classification system which Agassiz devised was based on dermal features such as these, so the (now lost) elements are recorded in the drawing.

A number of clear differences emerge between the drawings and the fossils as they are now. Slavish copying, or what would today be referred to as photo-realism, was not the aim of the illustrative work. Rather the intention was to show each fossil fish from a scientific, structural point of view. Frequent handling has taken its toll on some specimens such as the Dapedius colei Agassiz (right). Since Dinkel drew the original specimen in the mid 1830s (left), the delicate and fragile scales around the eye as well as the pectoral fin have been damaged or worn away. Fortunately the classification system which Agassiz devised was based on dermal features such as these, so the (now lost) elements are recorded in the drawing.

Additionally, although much effort was expended by the artist to draw a fossil in detail, the supporting matrix appears to have been of secondary value, so accuracy in this respect was not important. Indeed it was not uncommon for the surrounding rock shown in a drawing to be trimmed or removed entirely for the final lithographed version, generally to fit more neatly onto a page.

Additionally, although much effort was expended by the artist to draw a fossil in detail, the supporting matrix appears to have been of secondary value, so accuracy in this respect was not important. Indeed it was not uncommon for the surrounding rock shown in a drawing to be trimmed or removed entirely for the final lithographed version, generally to fit more neatly onto a page.

Nevertheless, there are more obvious reasons for differences between the supporting rock in the drawings and the fossil specimens. Fossils are frequently removed from their matrix for more detailed scientific study. In the case of the Early Devonian specimen Cephalaspis Lyelli Agassiz, parts of the rock have been mechanically chipped away. The NHM curator Arthur Smith Woodward noted in 1890 that since Agassiz’s original description the tail of the fish had been further extricated from the surrounding matrix, but unfortunately the crude process managed to destroy its opercular folds (gill covers).

COLLECTIONS’ FATE

While the private collections of figures like Enniskillen, Egerton and Gideon Mantell are now held by the Natural History Museum, the fate of other collections that provided specimens for Agassiz’s work has been mixed. For instance, the Geological Society’s own Museum collection was split up in 1911, and the French palaeontologist Eugenè Eudes-Deslongchamps’ (1830-1889) collection was destroyed during WW2.

Even Enniskillen’s collection did not escape unscathed. On its way to the soon-to-be-opened Natural History Museum in December 1882, thieves broke into the packing crates at Crewe railway station. The miscreants, disappointed by what they found, threw some of the collection into the River Dee.

This means that where a fossil no longer survives, Agassiz’s original artwork is an important and unique record.

- If you would like to help the Geological Society to conserve and digitise this valuable collection, or for further information about the fundraising appeal, please visit www.geolsoc.org.uk/sponsorafish.