Johnson, P., Dinosaur rustling in the Old West. Geoscientist

30 (3), 16-19, 2020

https://doi.org/doi: 10.1144/geosci2020-076,

Download the pdf here

Paul Johnson recounts the tale of the notorious ‘Bone Wars’

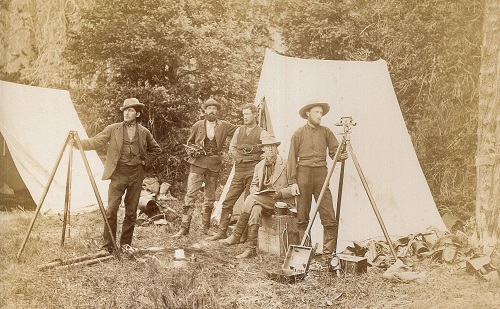

Left: USGS surveyors, c. 1870s. From the album Photographs of the principle points of interest in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Idaho & Montana (Geological Society of London Archives)

Left: USGS surveyors, c. 1870s. From the album Photographs of the principle points of interest in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Idaho & Montana (Geological Society of London Archives)

1876 was a momentous year for the expanding United States of America. Jesse James and his gang attempted their catastrophic bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota. The first transcontinental express railroad trip was made from New York to San Francisco. Wild Bill Hickok was shot in the back playing poker.

That year also saw the Battle of Little Bighorn and Custer’s Last Stand, themselves part of the great Sioux Wars that ranged across the Dakota Territory – the huge chunk of land in the American plains that the United States coveted but did not own. With the discovery of gold in the Black Hills prospectors moved into the area, and the US Government did very little to stop them. They trespassed upon land that the Lakota tribes considered sacred and even built the town of Deadwood to facilitate their adventuresome ways. For the space of a year in vast tracts of the West from Colorado north through Nebraska and Wyoming to Montana and Dakota, war raged between the indigenous Americans and the interlopers from the East.

It was all getting a bit too hot for some, most notably two men who’d been prospecting for the best part of a decade in the area and were already squabbling over their finds. For their workers and colleagues, the risk was too great; they retreated to places of greater safety. All geologists Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899) and Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897) could do, for a year at least, was to head back East to catalogue the vast piles of fossilised bones they had excavated, and produce their scientific papers.

Parallel careers

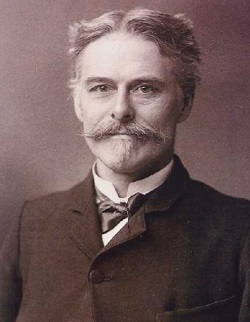

Right: Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897) Photograph taken c. 1885 by Frederick Gutekunst (public domain)

Right: Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897) Photograph taken c. 1885 by Frederick Gutekunst (public domain)

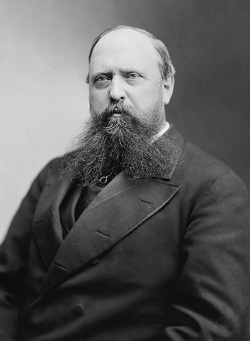

Othniel Marsh was the nephew of George Peabody, founder of J.P.Morgan and noted philanthropist. His uncle’s funds helped him through Yale University where he studied anatomy, mineralogy and geology, and on to Europe, to continue his studies in Berlin.

Edward Cope came from an orthodox Quaker family and had a father who doted on him. He pushed hard for the university education he received, finding himself re-cataloguing the herpetological collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences. Even at this young undergraduate age, he began publishing papers on the classification of various reptiles and amphibians. When the Civil War began, he too found himself travelling to Berlin. It was here that the paths of Marsh and Cope first crossed.

Initially they got on well, sharing dinners, touring the city and sharing their mutual love of palaeontology. Once they returned to their researches, they took turns naming new species after one another. But something clearly rankled both men about the other. Maybe it was the wealth and opportunity that Marsh possessed; perhaps it was Cope’s extensive record of publications at an early age. Whatever the reason, a brief period of amity was replaced by rumblings of hostility.

The rivalry intensifies

Left: Othneil Charles Marsh (1831-1899) Photograph taken between 1865 and 1880. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (public domain)

Left: Othneil Charles Marsh (1831-1899) Photograph taken between 1865 and 1880. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (public domain)

Both men returned to the US in the 1870s, drawn by the promise of large fossil finds. By now, their relationship had become tense, with the two publically attacking each other in papers and publications. Following a visit to a promising site in New Jersey, Marsh had secretly bribed pit operators to send news of any future fossil finds to him. Meanwhile, Cope found employment with Ferdinand Hayden’s Survey and took to prospecting for bones in areas that Marsh had previously considered his own territory. The rivalry grew - as did the number of finds emerging from the American West.

They argued in print about classification. They argued about naming. Most of Marsh’s names held, as did his classifications. The speed with which finds could be excavated, shipped, examined and described became critical; both men knew the other had made similar finds in similar locations and they could not risk being second in print. Both were working in territories where the law was weak and tempers fiery among those prospecting for riches. With the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, mines started opening - and where there were mines, there was the prospect of bones being found.

Dakota was dangerous territory. Marsh headed there with a large group, protected by soldiers. Cope found employment with the Army Corps of Engineers, but this limited him to finds where the Army was surveying. Marsh, meanwhile, could not only dig where he chose, but also championed the cause of the Lakota and gained the support of Chief Red Cloud, interceding where he could between the tribes and the army.

It was not to be successful. The pressure of speculators lead to the upheaval of 1876, and Marsh and Cope headed back East. Marsh would never to return West again. Their grudge would play out in elegant society, not in the streets of a Western settlement.

Como Bluff

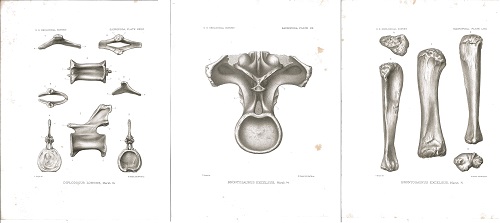

Right: Monochrome lithographs issued by the United States Geological Survey (1878-1899) depicting the bones of sauropods and brontotheres. Lithographed by E Crisand, New Haven, after drawings by Frederick Berger, under the supervision of Othniel Charles Marsh

Right: Monochrome lithographs issued by the United States Geological Survey (1878-1899) depicting the bones of sauropods and brontotheres. Lithographed by E Crisand, New Haven, after drawings by Frederick Berger, under the supervision of Othniel Charles Marsh

1876 was also a turning point for their discoveries. Colorado joined the Union that year and shortly thereafter Marsh and Cope received letters that something enormous was lurking beneath Como Bluff in that state. Marsh immediately paid his correspondent $100 to keep quiet; an expense that evidently had no effect, as Cope was informed by others.

Word was spreading that these two men would pay handsomely for old bones. Two construction workers on the Transcontinental railroad knew the area well and played Marsh off against Cope, raising the price of the information still further – but this was money well spent. Soon whole wagons full of bones were making their way to Yale – and these weren’t any old bones. They were the first specimens of Diplodocus, Allosaurus and Stegosaurus – hastily reconstructed, named and described by Marsh before the end of 1877. This was the motherlode of dinosaur fossils and Cope was not to be excluded. He instructed his men to spy and “rustle” Marsh’s dinosaurs out from under his nose.

Marsh may have had more money that Cope, but his payments were not always as speedy as his promises; those he had employed defected to the other side. Some employees grew fed up with the whole game, whilst others destroyed those bones they were unable to transport to prevent them falling into the hands of the other side. Paper after paper appeared in academic journals, some more hastily written than others. As the battle wore on, one of Marsh’s favourite tactics became to point out every single error he could find in Cope’s work and the speed both were working at lead to many errors – most famously, Cope’s botched reconstruction of the plesiosaur Elasmosaurus.

L eft: Gold mining in 1870s Blackhills, c. 1870s. From the album Photographs of the principal points of interest in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Idaho & Montana (Geological Society of London Archives)

eft: Gold mining in 1870s Blackhills, c. 1870s. From the album Photographs of the principal points of interest in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Idaho & Montana (Geological Society of London Archives)

Exposure

As the 1880s wore on, the skulduggery, shenanigans and outright criminality continued, and Marsh’s advantages of status and finance paid off as he drew ahead in the race to publish and collect. Cope would not let go, and saw his chance when his mentor, Ferdinand Hayden, retired from the fledgling United States Geographical Survey, and Marsh became a director. Cope went public, listing all of Marsh’s misdemeanours and taking testimony from employees regarding his behaviour. Cope had these accounts and records published by the decidedly non-academic journal the New York Herald. Palaeontology, or at least its practise, was suddenly front-page news, and the world was aghast.

Marsh and Cope’s personal grudge ended, not at high noon on a dusty main street, but in the universities of the eastern US. Marsh lost his position and the USGS. Cope began to suffer increasingly bad health. The war ran out of steam, leaving two angry and shattered men and a wide variety of discoveries the like of which the world had never seen before.

Their lifelong feud had a strange coda. Before his death in 1897, Cope challenged Marsh to leave his brain to science so that those of both men might be weighed and measured, to ascertain once and for all which had been the biggest. Unsurprisingly, Marsh declined, but Cope’s skull reportedly remains in the collection of the University of Pennsylvania, along with many of his finds.

Paul Johnson is Map Librarian at the Geological Society