As geologist and science writer Nina Morgan discovers, there are some things only a women can do...

Geoscientist 20.10 October 2010

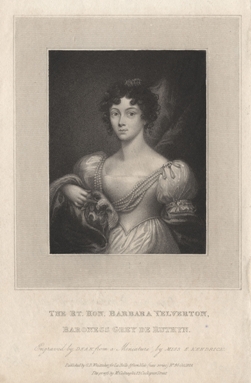

Even though the scale of the achievements female fossil collectors such as Mary Anning and Elizabeth Philpot are now becoming more widely appreciated, there remains a lingering impression that the significant contributions to palaeontology made by women in the 19th Century are more the exception than the rule. The social mores of their time dictated that however intelligent, members of the gentler gender were not viewed to be as physically tough as their male counterparts. But as a collection of letters from Barbara Hastings, Marchioness of Hastings (1810-1858) housed in the Natural History Museum in London reveals women in the 19th century could – and did – demonstrate a scientific determination that belied their designation as the weaker sex.

Although self-taught, and noted for her taste for gambling and her racy aristocratic lifestyle, Hasting turned herself into a palaeontologist who was respected by many of her male contemporaries. Her stamping grounds included the Eocene deposits of Hordle Cliff near Lymington on the Hampshire coast, and for six productive years she devoted her life to the collection, preparation and recording of the fossil vertebrates she discovered there. She built a museum as an extension to her home that housed several thousand fossil specimens, discovered several new species of crocodile as well as the tortoise, Trionyx barbarae, which was named after her. She also published three academic papers about her work under her own name and presented her findings at the British Association meeting in Oxford in 1847.

"She was a 'fossilist' who knows her work", wrote the geologist Edward Forbes, who also noted that she was "one of the most excellent (and without exception the cleverest) women I ever met." The anatomist and vertebrate palaeontologist Richard Owen was another great admirer. He was also a frequent correspondent, and it was to him that she revealed her true devotion to science. Explaining the delayed arrival of some fossil specimens she wrote to him saying, "Were I in travelling condition I wd bring up my treasures myself, but as in two months time I am expecting my confinement, I am compelled to be quiet." But not one to let 'minor' events like pregnancy hold her back she wrote to Owen again to say: "I expect to be confined the end of next week ... are you likely to want any series of crocodile bones before I am about again in the month of February?"

Once her daughter was born, she contacted Owen again to enquire whether some Trionyx specimens "which I packed up only a few hours before my baby was born – all arrived safe" "I am dying to resume my labours – in the geological line," she continues. Now that's a level of determination none of her male colleagues could hope to emulate!

Acknowledgements

The idea for this vignette and the quotes from Barbara Hastings' letters quotes were taken from an article entitled: Barbara Hastings: the first lady of fossils by Karolyn Shindler, which appeared in the Daily Telegraph on 15 June 2010. I am grateful to Karolyn Shindler for also providing additional background information.]

- If the past is the key to your present interests, why not join the History of Geology Group (HOGG). For more information and to read the latest HOGG Newsletter visit the HOGG website at: www.geolsoc.org.uk/hogg. A HOGG conference on Geological Collectors and collecting is planned for 4-5 April 2011 at the Natural History Museum, London. To receive further information and announcements about the conference, e-mail: [email protected]

Nina Morgan is a geologist and science writer based near Oxford.