We hear a lot about artisanal mining - none of it good. Addressing its many challenges needs a step-change in education, says Felix Toteu.*

Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining is mining by individuals, groups, families, or cooperatives with minimal or no mechanization, often informally and/or illegally. Typically it is manual and labour-intensive, using only picks, shovels and basins, or else with some heavy machinery employed on a small scale1. In Africa ASM has become an important economic activity in rural areas, even overtaking subsistence agriculture.

Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining is mining by individuals, groups, families, or cooperatives with minimal or no mechanization, often informally and/or illegally. Typically it is manual and labour-intensive, using only picks, shovels and basins, or else with some heavy machinery employed on a small scale1. In Africa ASM has become an important economic activity in rural areas, even overtaking subsistence agriculture.

Picture: African artisanal mining camp. All photos - UNESCO

This growing trend in sub-Saharan African countries is transforming the sector into a business bringing both benefits and challenges that demand proper attention from governments – especially when they have a bearing upon Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Many African governments have begun to formalise the sector, and in September 2015 UNESCO organised a workshop in Arusha (Tanzania) to look into the ASM formalisation, with a view to identifying research and training gaps.

The workshop concluded that there was a need to advocate, develop and implement ASM-specific training curricula in African mining schools. Unlike the currently familiar project-driven and donor-dependent models, the proposed training initiative will be embedded in national education systems, so as to guarantee a sustainable supply of skills that the growing African ASM sector needs in order to be transformed.

Africa

Africa hosts more than one third of the world’s mineral resources, and much of the continent has yet to be properly surveyed. Ensuring appropriate exploitation of these resources could bring sustainable development benefits to large parts of the continent.

In 2010, mining in Africa amounted to a modest 8% of the total global mineral exploration and extraction budget2. Across the continent, ASM operators produce more than 35 different minerals, with emphasis on ‘high-value low-volume’ minerals such as gold, coltan, and precious and semi-precious gemstones including diamonds3. ASM contributes significantly to the economic development of countries where it is prevalent. In some, like Rwanda, it constitutes the only form of mining activity, whereas in Nigeria it accounts for 90% of solid mineral production .

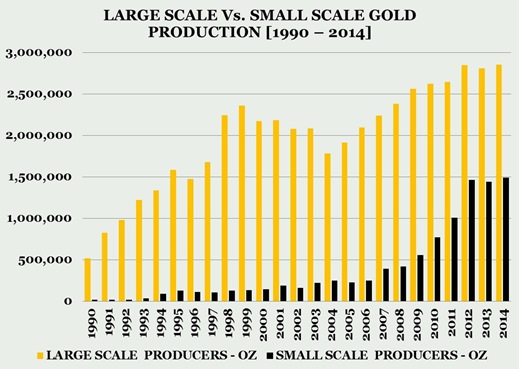

Figure 1: Large scale vs small scale gold production 1990-2014

Figure 1: Large scale vs small scale gold production 1990-2014

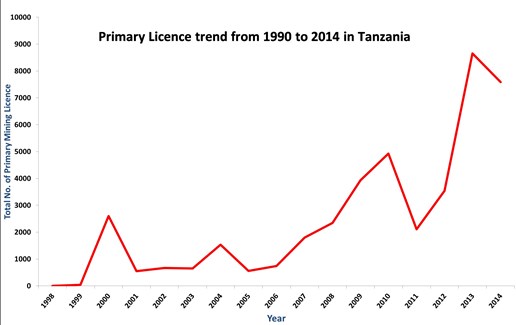

Ghana has recorded a constant increase of ASM’s share in gold production4 (Fig. 1). Tanzania has experienced a surge in ASM licensing in recent years (Fig. 2), involving about two million operatives (2014), up to 28% of whom are women5. The African Mineral Development Centre (AMDC) estimates that in all, 12 million people work in the sector, supporting a further 60-100 million direct dependents and six million service providers (who in turn have 30 to 35 million dependents of their own)6. The increasing trend is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

Across Africa, most Governments recognise ASM’s importance to remote rural economies, and the fact that in most such communities, mining is one of the only viable income-generating activities. ASM generates other ancillary economic activities, such increased food production (to supply the miners); trade (especially food and beverages) and local transport services between the site and neighbouring villages. Finally, high economic growth rates in much of Africa have boosted demand for industrial and construction material (‘low-value mineral and material’) thus creating even more jobs.

Negative impacts

But governments also recognise the downside. ASM can have negative impacts, ranging from criminality and illegality to significant harm to health and safety - of miners, communities, and the environment. Because of a lack of training and technical understanding, many operations pollute water supplies and degrade agricultural land. Opening up previously pristine areas to mining often means deforestation, habitat fragmentation and conflict over land-use. New ASM often results in migration of peoples, sometimes from neighbouring countries - straining social infrastructure, increasing crime, prostitution and sexually-transmitted diseases including HIV, drug and alcohol abuse, and disrupting local culture.

Figure 2: Primary licence trend 1990-2014, Tanzania

Figure 2: Primary licence trend 1990-2014, Tanzania

There is significant evidence that ASM activities have also fuelled large-scale conflict, destabilisation and wars; leading to the international focus on closing down the supply-chain of so-called ‘conflict minerals’. Then there is the dangerous use of substances such as mercury and cyanide. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates6 that 37-40 % of the mercury released to the environment comes from ASM for gold. The Minamata Convention on Mercury7 requests that signatory countries develop National Action Plans (NAP) for reducing mercury use. This is already on track in a number of African countries. Formalising ASM, and implementing the Minamata Convention, provide an opportunity for research into mercury-free technologies, and training for ASM operators in reducing the negative health, safety and environmental consequences of their activities.

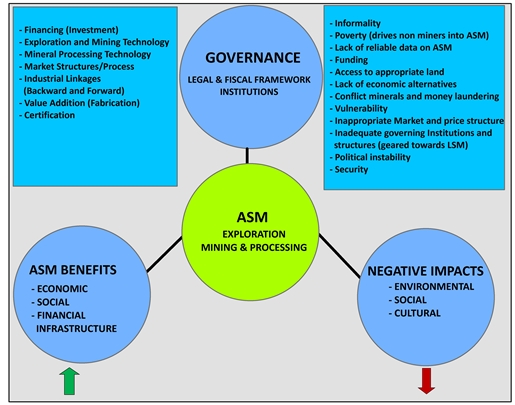

The AMDC has conducted a study featuring ASM, drawing on evidence from 16 countries where ASM contributes significantly to the local economy8 (Fig. 3). Its recommendations stress “harnessing of the potential of artisanal and small-scale mining to stimulate local/national entrepreneurship, improve livelihoods and advance integrated rural social and economic development” while at the same time minimising negative impacts.

Global initiatives

The African Union and partners have embarked on an ambitious initiative ̶̶ the ‘African Mining Vision’9 ̶ which aims to transform the mining sector into an engine for sustainable development, especially in rural areas. A specific part of this vision is devoted to ASM, and aims “to create a mining sector that harnesses the potential of artisanal and small scale mining to advance integrated and sustainable rural socio-economic development”.

Figure 3: Artisanal mining governance, benefits and disbenefits. From AMDC study drawing on evidence from 16 countries where ASM contributes significantly to the economy.

Figure 3: Artisanal mining governance, benefits and disbenefits. From AMDC study drawing on evidence from 16 countries where ASM contributes significantly to the economy.

Besides regulatory and fiscal measures, the Implementation Plan identifies ‘skill development’ as a crucial element. This makes it essential to develop, at country level, training strategies targeting both the miners themselves (to trigger a change of behaviour) and government officials (to promote the creation of a cadre of skilled staff, capable of managing the sector).

A consortium (comprising Columbia Centre on Sustainable Investment (CCSI), the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), UNDP, and the World Economic Forum) has already published a preliminary atlas, mapping mining to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)10. The atlas focuses on Large Scale-Mining, but recognises that ASM has impacts on several Goals - including SDG1 (‘End Poverty’), SDG3 (‘Good Health and Well-Being’), SDG8 (‘Decent Work and Economic Growth’), SDG15 (‘Life on Land’), and SDG16 (‘Peace and Justice; Strong Institutions’).

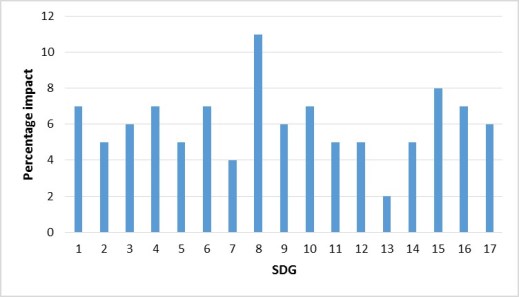

Following the UNESCO workshop in Arusha, we now understand that ASM activities entail opportunities and/or challenges in achieving (in one way or another) all 17 Goals! The accompanying histogram <Figure 4> illustrates the level of ASM impacts on each (though highlighting Goals 1, 2, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 15). This confirms what we already know about the effect of ASM on various socio-economic sectors. Harnessing these opportunities, while addressing the challenges of ASM, will require that countries adopt a cross-sectoral approach – as well as cooperation between different ministries and stakeholders.

Similarly, some SDGs impose constraints - which artisanal miners consider as detrimental to their activity. Governments will have to consider trade-offs in the formalisation process (to avoid achieving one specific goal at the expense of others) and thus make sure that ASM is truly beneficial to communities, governments and the environment. This will be crucial where ASM competes with agriculture, for example, or where ASM endangers ecosystems and health. Education must be at the core of formalisation strategy.

Research, training, legislation

Research activities supporting ASM are limited everywhere, but particularly in Africa. A few technical research projects have focused on critical ecosystems in protected areas (e.g., Liberia, Gabon and Madagascar)11. A number of socio-economic studies have provided better understanding of ASM communities, the role of ASM operators and gender-related concerns12, 13. However, very few African schools for mining engineers feature ASM in their curricula (though one module is offered at the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria; MINTEK (South Africa) also has an ASM training initiative). Globally, schools of mining engineering traditionally focus on Large-Scale Mining. Consequently it comes as no surprise that most ASM training in Africa currently occurs through externally-funded projects14.

Figure 4: Level of ASM impacts on each of the 17 UNESCO goals

Figure 4: Level of ASM impacts on each of the 17 UNESCO goals

ASM has been incorporated in revised mining legislation and regulations over the last decade. This has created a need to train government officials at national, provincial and district level to understand and manage the sector. Often, this training has to date been associated with projects funded through loans or grants. To take a few examples from the many available - the World Bank has a component for ASM in its country-specific ‘mining programs’; in 2015, the European Union provided €13 million to support ASM training in African, Caribbean and Pacific states. Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda have recently received funds from DFID, and so on15.

However there has been so far no detailed assessment of the impact that these training initiatives have had (or not had) on the African ASM sector. While acknowledging short–term positive impact, it is apparent that this project-driven, donor-dependant funding has been very challenging for the projects’ sustainability16. To deepen understanding of their real impact, UNESCO now intends to carry out an assessment of some major project-driven training initiatives, so as to build a more detailed picture of what went well (or wrong).

ASM on the curriculum

Academic input into ASM in Africa has been more about research than training, typically focusing on legal, financial and beneficiation aspects. There remains an urgent need to guarantee a supply of skills to the sector, and current approaches are not sufficient for this task. Indeed, the lack of strategy towards sustainability and ownership has been detrimental to many training initiatives in the ASM sector in Africa.

UNESCO believes that sustainability and ownership will come if an ASM-specific training approach is embedded in national education systems, becoming part and parcel of the normal training of mining engineers and technicians. But achieving this will demand commitment from governments. We might learn from the recent success of agriculture in rural Africa, which has been largely brought about by government investment in agricultural training, especially in schools for agricultural engineers and in agricultural Technical Vocational schools.

UNESCO’s model

Implementing the recommendations of UNESCO’s Arusha workshop requires a robust policy toward research-based training, especially in areas that enhance the efficiency of mining and processing, to care for environmental and community health, and to achieve maximum national and international benefits.

Implementing the recommendations of UNESCO’s Arusha workshop requires a robust policy toward research-based training, especially in areas that enhance the efficiency of mining and processing, to care for environmental and community health, and to achieve maximum national and international benefits.

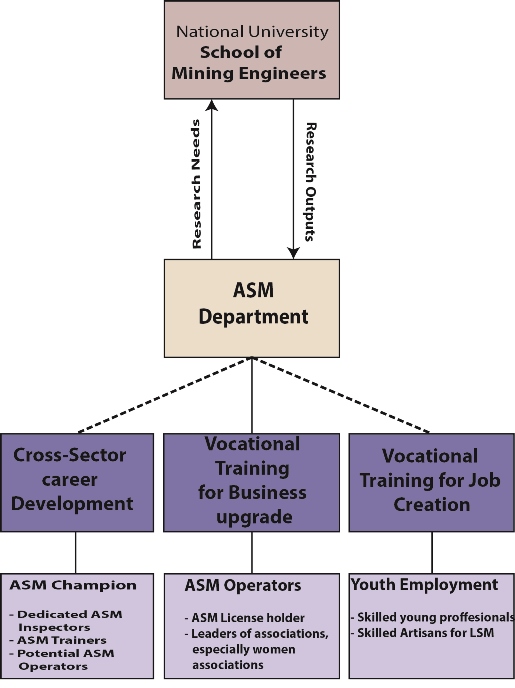

Figure 5: Proposed research-based training will be offered in a university with recognised capacity in mining – to safeguard quality, and benefit from research outputs

The UNESCO model relies on the belief that excellence in training results from excellence in research, and that this synergy is best realised in universities. The proposed research-based training (Fig. 5) will therefore be offered in a university with recognised capacity in mining – both to safeguard the quality of training, and to benefit from research outputs (e.g., innovation and design of affordable and locally maintainable technologies, value addition, mineral beneficiation, etc.).

The course will last one semester and be recognised by certificates of competence. Training will be aimed at three distinct audiences. At one end of the spectrum, it will focus on job creation and youth employment, working with local vocational training institutions (extensions of hosting universities) in rural areas - developing entry-level competency training for potential ASM operators.

At the other end, strategic and leadership skills will be developed, to allow the sector to flourish. This will target professionals (‘ASM Champions’)17 who have already been operating in the sector all their careers and are looking to upgrade and expand their knowledge and competence in an inter-disciplinary way. A new cohort of dedicated inspectors for ASM will eventually arise from this group.

In the middle of the spectrum, training will focus on associations and ASM operators seeking to upgrade their businesses. To address the gender gap in the sector, special attention will be given here to developing female ‘drivers of change’, who will work to improve women’s associations. Training will take place on-campus. However, it will be necessary to establish off-campus vocational training centres as annexes of the hosting university, preferably in important mining areas - so as to reach out to associations of miners and address the gender gap and youth employment in rural areas.

In the middle of the spectrum, training will focus on associations and ASM operators seeking to upgrade their businesses. To address the gender gap in the sector, special attention will be given here to developing female ‘drivers of change’, who will work to improve women’s associations. Training will take place on-campus. However, it will be necessary to establish off-campus vocational training centres as annexes of the hosting university, preferably in important mining areas - so as to reach out to associations of miners and address the gender gap and youth employment in rural areas.

ASM is a proven driver of socio-economic development but, at the same time, a threat to the environment and to community health. To take full economic advantage of ASM and reduce its negative impacts, behaviours must change. UNESCO believes education must play a crucial role, and that governments must therefore take the necessary political and financial steps to invest in it.

This commitment will encourage private-sector, international organisations and donors to join and support the initiative. Building on lessons learnt from the current research-oriented UNESCO-Sida project on Abandoned Mines, UNESCO sees this training initiative as the next step towards transforming ASM in Africa, and will work to promote the development and incorporation of a curriculum specific to ASM in the normal training of mining engineers and technicians.

The proposed way forward has three phases. First, we are currently working to assess the past decade’s training and how it has impacted on the African ASM sector. Second, we will engage in discussions with selected African universities with proven training and research capacity on how best to incorporate a curriculum specific to ASM in the normal training of mining engineers and technicians. We expect that such a curriculum will take into account the regional context, cover the whole spectrum of ASM activities ̶ precious metals, gemstones, and industrial and construction material ̶ from mining operation to value addition, and target all or part of the three audiences (ASM Champions, ASM operators and youth employment). Third, the findings of the above assessment and consultations will serve as the basis for a proposal to potential donors to support four-year pilot schemes in a few countries, giving time for hosting universities to prepare for full ownership and embedding within national education systems.

Acknowledgements

During the workshop in Arusha, a Working Group was set up to prepare the document on which this article is based. UNESCO Nairobi convened a meeting from 10 to 12 December 2015 at the Centre for Sustainability of Mining and Industry (CSMI) of the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg (South Africa) to prepare a preliminary draft. Participants included: Caroline Digby, CSMI, South Africa; Priscus Kaspana, Geological Survey of Tanzania; Salvador Mondlane Junior, Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique; Simon Nibizi, International Conference of Great Lake Region, Burundi; John Tyschen, Geological Survey of Denmark; and S. Felix Toteu, UNESCO Nairobi. The document was finalised by Felix Toteu in July 2016.

During the workshop in Arusha, a Working Group was set up to prepare the document on which this article is based. UNESCO Nairobi convened a meeting from 10 to 12 December 2015 at the Centre for Sustainability of Mining and Industry (CSMI) of the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg (South Africa) to prepare a preliminary draft. Participants included: Caroline Digby, CSMI, South Africa; Priscus Kaspana, Geological Survey of Tanzania; Salvador Mondlane Junior, Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique; Simon Nibizi, International Conference of Great Lake Region, Burundi; John Tyschen, Geological Survey of Denmark; and S. Felix Toteu, UNESCO Nairobi. The document was finalised by Felix Toteu in July 2016.

* Sadrack Felix Toteu Hon. FGS, is Earth Science Programme Specialist at the UNESCO Regional Office for Eastern Africa, Nairobi, Kenya. E: [email protected]

References

- POLINARES working paper n. 19, March 2012.

- IFC, 2014.

- AMDC Report 2015

- Nigerian Ministry of Mines and Steel Development 2015.

- Tanzania Mineral Commission, UNESCO ASM Workshop in Arusha 2 to 5 September 2015

- UNEP, 2013 on Global Mercury Assessment: sources, emissions, releases and environmental transport. UNEP Chemicals Branch, Geneva, Switzerland.

- http://www.mercuryconvention.org/Portals/11/documents/conventionText/Minamata%20Convention%20on%20Mercury_e.pdf

- ECA publication in preparation

- http://www.africaminingvision.org/amv_resources/AMV/Africa_Mining_Vision_English.pdf

- http://unsdsn.org/news/2016/01/13/mining/

- World Bank, Africa Region: http://www.profor.info/sites/profor.info/files/docs/ASM-brochure.pdf

- Hoedoafia, M A, 2014. The Effects of Small Scale Gold Mining on Living Conditions: A Case Study of the West Gonja District of Ghana, International Journal of Social Science Research: 2, p152-164.

- African Women in Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining, Special Report by AMDC reprinted from New African Women magazine, February/March, 2015.

- http://cirdi.ca/programming/itcam/

- www.artisanalgold.org

- Ethiopian Gemstones, Maximizing Potential, DFATD 2014.

- ‘ASM champions’ are individuals with the relevant skills, networks, and broad understanding of the sector, which equips them to drive positive change in the ASM sector. They may sit in a government office, in a business along the supply chain or in industry.