Carbonate sedimentologist who defined his profession and was one of the most influential thinkers in the field.

Carbonate sedimentologist who defined his profession and was one of the most influential thinkers in the field.

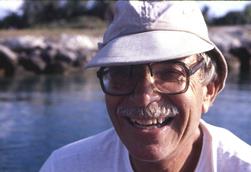

Bob Ginsburg was a geologist who studied carbonate sediments, their genesis, deposition, and transformation into mature rocks. He defined the profession of carbonate sedimentology and was one of the most influential thinkers in his field, working in both industry and academia, retiring at the age of 85.

His career began in 1950 when he left the University of Chicago to become a research assistant at the University of Miami’s Marine Laboratory, the precursor of the present Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. Subsequently he moved first to establish and lead a research and training program on carbonates for the Shell Development Company (1954–64), then to become Professor of Geology and Oceanography at The Johns Hopkins University (1965–70).

Miami

In 1970, he was persuaded by Cesare Emiliani to come back to the University of Miami as Professor of Sedimentology. At that time, he organized the T. Wayland Vaughan Laboratory for Comparative Sedimentology headquartered on ocean-facing Fisher Island at the entrance to the Port of Miami. In 1991, the University sold Fisher Island and Bob moved fulltime to the RSMAS campus. At RSMAS, he continued to develop and pursue new avenues, exchanging his role as head of the Sedimentology Laboratory for an effort to spearhead the assessment of declining coral reefs in the Caribbean. In this new direction, he touched an entire new generation of scientists.

His first published paper appeared soon after his arrival in Miami, ‘Intertidal Erosion on the Florida Keys’ (1953). It was a harbinger of his future career as it questioned the prevailing chemical explanation for shoreline erosion by offering a biological alternative. In the following half century, with his associates, post-doctoral fellows and students he has authored a series of seminal papers, books and reports on the links between contemporary and Holocene processes and products of carbonate deposition and their fossil counterparts.

Dolomite

These publications have ranged from the formation of dolomite, precipitation of cements in reefs, health of coral reefs, sedimentation and history of carbonate platforms, and stromatolites. These studies, combined with countless field trips and lecture tours in North America, Europe, North Africa and Australia, have had a significant worldwide influence on research, teaching and the petroleum potential of carbonate deposits. A measure of this impact is the award of Fellowship in the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Geological Society of America, the Twenhofel Medal of the Society for Sedimentary Geology, the Sorby Medal of the International Association of Sedimentology and honorary membership in four professional societies

While his impact on his profession has been immeasurable, he has also been an inspiring teacher and the principal adviser for more than 20 graduate students as well as numerous postdoctoral associates. While some of his students and postdocs stayed at home in Miami, others have become distinguished teachers and geologists throughout the world. It would almost be understated to say that Bob Ginsburg’s influence upon the study of carbonate environments has been immeasurable.

By Peter K Swart

A longer version of this obituary follows. Editor.

On July 9, 2017 a geological legend, Robert Nathan Ginsburg died. Bob defined the profession of carbonate sedimentology and was one of the most influential thinkers in his field working in both industry and academia. Born in 1925, Bob has had a profound influence on how we search for oil using the Modern in order to understand the past. Bob’s geological career began in 1950 when he left the University of Chicago to become a research assistant at the University of Miami’s Marine Laboratory, the precursor of the present Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science (RSMAS). He eventually obtained a PhD from the University of Chicago where some of his professors were Francis Pettijohn and Heinz Lowenstam, and his contemporaries included Cesare Emiliani, Keith Chave, Paul Potter, Ray Siever, Jerry Wasserburg, Irving Friedman, Harmon Craig, and others.

Upon leading a field trip to South Florida in the early 1950s, Bob so impressed the Shell Development Company that he was hired to establish a laboratory with the then astonishing idea that the study of Modern environments might actually help find oil in ancient carbonate rocks. Together with Mike Lloyd Bob established the “Coral Gables Office” of Shell Development and a mafia of carbonate workers ensued. This was the golden age of carbonate research with the office being visited regularly by 100s of geologists and it was acknowledged that the work of Bob and his team significantly influenced the direction of oil exploration. During this time, Bob met and married Helen, a teacher of creative writing at the University of Miami. In 1965, Bob moved to Baltimore where he was reunited with Pettijohn and became Professor of Geology and Oceanography at The Johns Hopkins University (1965–70). Here he worked at the Bermuda Biological Station and conducted a detailed study of the Andros tidal flats with Laurie Hardie.

In 1970, he was persuaded by Cesare Emiliani to return to the University of Miami as a Professor of Sedimentology. At that time, The University of Miami had just acquired a long-term lease on a disused quarantine station on 15 acres of ocean-facing Fisher Island at the entrance to the Port of Miami. Back then, Fisher Island was empty except for the old Vanderbilt mansion, an empty mausoleum with the words Fisher on it, and the seven buildings comprising the quarantine station. Here Bob established the T. Wayland Vaughan Laboratory for Comparative Sedimentology, using one building for a dormitory, one for workspace, and one for an office. Getting to the island could be a challenge. Every morning at 8:30 a.m. a small ferry would pick up the students, staff, and professors from the tip of Miami Beach for the two minute crossing dodging the odd ocean liner or suspiciously heavily laden speed boat. The ferry went regularly every hour, but stopped at 4:30 p.m. meaning students frequently had to stay the night (if they were serious in getting their work done) in the dormitory. There were always plenty of cockroaches for company. The University also leased one of the remaining buildings to the United States Geological Survey where Gene Shinn, one of the original Shell Mafia, and his associates established a small branch office and planned their studies of coral reefs, whitings, and other carbonate phenomenon. They interacted spiritedly with Bob and his happy band of students, staff, and postdoctoral associates. Wolfgang Schlager, Noel James, and Gregor Eberli were among the notable associates at Fisher Island during this time. Visitors included a who is who of sedimentary geology, Bathurst, Hardie, Wilson, Myers, Read, Wilkinson, Kastner, Siever, Potter to name but a few. One of the many great traditions of Fisher Island was to plant a tree for every student, staff, or scientist who spent time there and was moving on.

When we finally vacated the island in 1991, it was a forest. Coincident with the sale of Fisher Island, the demolition of the buildings and the conversion of our utopia to expensive condos, Bob embarked on one of his most ambitious projects, the drilling of two deep boreholes near the margin of Great Bahama Bank. The goals of the project were to test the interpretations made from seismic lines that he had manage to convince Texaco to give him. These lines showed that the shape of the Bahamas had not always the same as it appears now. Rather Great Bahama Bank had been composed of a number of smaller platforms, which had over millions of years merged together. Was this true and if so, how long did this take? Answers to these questions (and much more as we learned later) could only be provided by drilling. Bob and myself wrote a proposal to the National Science Foundation in 1989 and with the help of a 33% contribution from industry drilled two cores from a jack up barge positioned in 8 m of water along the seismic line. We had many adventures during the drilling that was challenging to say the least. Communication for example was by single side band radio and during one exchange when Bob was trying to purchase something vital for the drilling he broadcast his credit card number hoping he would not be over heard. Unfortunately for him someone was listening, with a pen in hand. Eventually we retrieved over 1000 m of cores with near perfect recovery. Years later these cores, together with an extension of the transect into the Straits of Florida where five other holes were cored using the JOIDES Resolution, continue to provide new insights into the history of the Bahamas.

Post Fisher Island and now at the RSMAS campus of the University of Miami on Virginia Key, Bob continued to develop and pursue new avenues of study. Bob had always maintained a strong interest in coral reefs, having organized the 1977 International Coral Reef Symposium in Miami. Now concerned about the apparent decline of corals reefs throughout the Caribbean he exchanged his role as head of the Sedimentology Laboratory for an effort to understand the origin of this tragedy. He soon discovered that there was an appalling lack of baseline data that could be used to document the perceived decrease so he set up a simple protocol which could be used by amateurs and professionals alike to survey reefs in a rapid quantitative manner. With these data obtained over a number of years the ugly truth about the decline in coral reefs could not be ignored. In this new direction, he touched an entirely new generation of scientists. Bob finally hung up his hammer and fins in 2011 at the age of 85.

Miami

Bob’s first scientific paper appeared soon after his arrival in Miami in 1953. Entitled ‘Intertidal Erosion on the Florida Keys’, it was a harbinger of his future career as it questioned the prevailing chemical explanation for shoreline erosion by offering a biological alternative. In the following half century, with his associates, post-doctoral fellows and students he has authored a series of seminal papers, books and reports on the links between contemporary and Holocene processes and products of carbonate deposition and their fossil counterparts. These publications have ranged from the formation of dolomite, precipitation of cements in reefs, health of coral reefs, sedimentation and history of carbonate platforms, and stromatolites. These studies, combined with countless field trips and lecture tours in North America, Europe, North Africa and Australia, have had a significant worldwide influence on research, teaching and the petroleum potential of carbonate deposits. A measure of this impact was the award of Fellowship in the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Geological Society of America, the Twenhofel Medal of the Society for Sedimentary Geology, the Sorby Medal of the International Association of Sedimentology and honorary membership in four professional societies

One of Bob’s most impressive contributions to geology was his ability to ask the “So what?” question. A field trip with Bob was not merely descriptive, but interrogative. “What do suppose this is?” “Umm…” “Do you suppose that…?” “What does this tell us?” . In the lab I would proudly describe my accomplishment for the day only to be faced with the “so what?” question. Irritating as it was it would force one to reexamine the rationale for performing an experiment and delve deeper into its significance.

While his impact on his profession has been immeasurable, he has also been an inspiring teacher and the principal advisor for more than 20 graduate students as well as numerous post-doctoral associates. Naming them all here would be a folly as I might forget one. While some of his students and post-doctoral associates stayed at home in Miami, others have become distinguished teachers and geologists throughout the world. It would almost be an understatement to say that Bob Ginsburg’s influence upon the study of carbonate environments has been immeasurable.

Peter K. Swart

Miami July 2017