|

Extract fom John Martin's doom-laden frontispiece to Thomas Hawkins' 'The book of the great sea-dragons, Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri ... gedolim taninim, of Moses', (1840). GSL Library collections.

|

The deeply eccentric Thomas Hawkins (1810-1889, GSL Membership no.932) is best known today for his extraordinary collection of ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs which are now held by the Natural History Museum. Most were excavated from quarries in Street, Somerset, but included in the collection were a number of specimens associated with Mary Anning.

Fresh from his election as a Fellow of the Geological Society the previous month, Hawkins had made his way down to Lyme in July 1832. There he first met Mary Anning who had just found the skull of an ichthyosaur. Hawkins purchased the specimen but was interested in the rest of the animal:

"Accompanying Miss Anning the next morning on the beach, she pointed out to me the place whence it was brought. Persuaded that the other portion of the skeleton must be there, I advised its extraction, if it were possible, but Miss Anning had so little faith in my opinion, that she assured me I was at liberty to examine its propriety or otherwise myself. Hereupon I waited upon Mr Edwards, the owner of the land, and requested permission to throw down as much of the cliff as was necessary for such intention, which he very handsomely allowed me to do." From Thomas Hawkins, 'Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, extinct monsters of the ancient earth...', (1834).

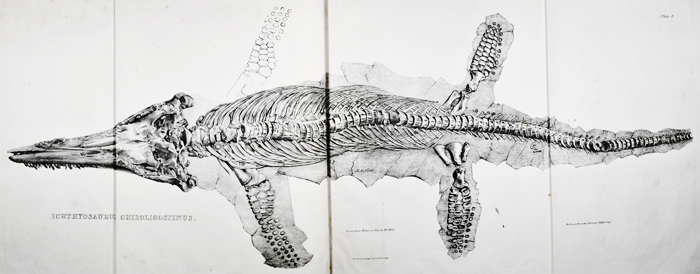

'Chiroligostinus’ was the species name Hawkins gave to his ichthyosaur (Anning identified it as Ichthyosaur platydon, now Temnodontosaurus platyodon). Hawkins would also later abandon the genus ichthyosaur to rename it Oligostinus chiroligostinus. The name did not catch on.

Given free rein to excavate the rest of the skeleton for himself, Hawkins hired some local men with spades and pick-axes to dig out the specimen. According to his account, it took three days’ work to shift over 20,000 loads of earth, taking down part of a cliff in the process and attracting crowds of sightseers eager to see the results. However Hawkins’ joy at excavating the creature was short lived as the specimen began to break up almost immediately. Help was at hand:

"Ah but the tug of war!- the bones with the marl in which they lay, broke into small fragments, so that I almost despaired of their re-union; albeit, with the kind assistance of Miss Anning, the whole of them were packed, and by night-fall the last heave box-full was deposited in a place of safety. So secured, the skeleton and its matrix weighed a ton." From Thomas Hawkins, 'Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, extinct monsters of the ancient earth...', (1834).

|

The complete 'Ichthyosaurus chiroligostinus' , the skull excavated by Mary Anning the rest by Hawkins in 1832. It is one of the largest and most complete Lower Jurassic ichthyosaurs known with a total length of 6.83 metres. Plate from T Hawkins, 'Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, extinct monsters of the ancient earth...', (1834). GSL Library collections.

|

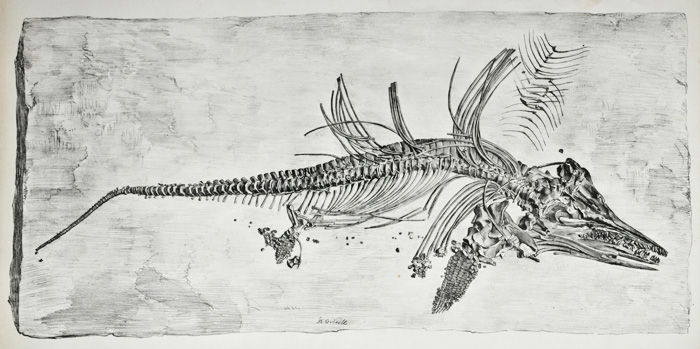

The following year, Hawkins was back. Another local fossilist, Jonas Wishcombe from Charmouth, had pointed out a further ichthyosaur embedded on the fore-shore between Lyme and Charmouth. Wishcombe had known of the existence of the fossil for some months but had not been able to extract it. Hawkins was in the process of purchasing the rights to the skeleton for a guinea, when Mary Anning interrupted him:

'"You will never get that animal", said Miss Anning...or if you do per-chance, it cannot be saved." My eyes glare upon the intellectual countenace before me, - the words of those lips were I knew as oracular as those of a Pythoness and my heart fainted within me. She saw my change of blood and stopped - "because the marl, full of pyrites1, falls to pieces as soon as dry...that I can prevent. Can you."' From Thomas Hawkins, 'Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, extinct monsters of the ancient earth...', (1834).

Hawkins had to wait a few weeks until the weather had cleared, bumping into Anning on his way down to the shore telling him to "Make haste; the tide's going out fast." Hawkins and his team of men managed to extract the specimen the same day but as Anning had predicted the marl, as soon as it dried, cracked but it was saved by placing it in a tight wooden case secured with plaster.

|

Hawkins' Ichthyosaurus chiropolyostinus which was excavated in the autumn of 1833, from T Hawkins, 'Memoirs of Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri, extinct monsters of the ancient earth...', (1834). GSL Library collections

|

Hawkins sold his collection in two parts to the British Museum in 1834 and 1840 for the combined sum of £3115 5s (equivalent to over £188,000 in today’s money). However, not all was what it seemed. During a Select Committee hearing on the Condition, Management and Affairs of the British Museum held in 1835, it was found that Hawkins was fond of restoring his specimens with plaster. During the hearing, the Select Committee focused on the largest specimen - the Ichthyosaurus chiroligostinus - which by the time of its sale to the British Museum had acquired a new front paddle and had its missing vertebrae replaced.

Whilst the Trustees and the curators of the British Museum were shocked, Hawkins’ practices amongst the geological community were well known. As Mary Anning remarked in a letter to Charlotte Murchison:

“... “if Mr Hawkins has set the last specimen if Icht platydon as it lay in the cliff it will be a most magnificent specimen, but he is schuch an enthusiast that he makes things as he images the[y] ought to be; and not as they are really found, the platydon that I in part gave him was to large for my poverty & I would have not have trusted to his making up, though very much broken it might be made a splendid thing without any addition.” Extract from letter from Mary Anning to Charlotte Murchison, 11 October [?1833]. Archive ref: LDGSL/838/A/7/3.

Notes:

1. Iron pyrite is a common mineral composed of iron and sulphide (FeS2) and when exposed to humidity, the sulphide component oxidizes to form, amongst other things, sulphuric acid which can break down the matrix of a fossil.

<<Back to main page

Next: Later years and friendships>>