Hazel Gibson and Iain Stewart explore the United States experience of shale gas extraction*

Over the course of April and May 2011, the UK public became aware of a new word: ‘fracking’. Its arrival was heralded by a flurry of small earthquakes near Blackpool. This mild seismic fanfare (the largest event being M 2.3) at Preece Hall was quickly attributed to gas drilling close by at Becconsall, where the operators were testing the technique properly referred to as ‘hydraulic fracturing’.

PRESSURE

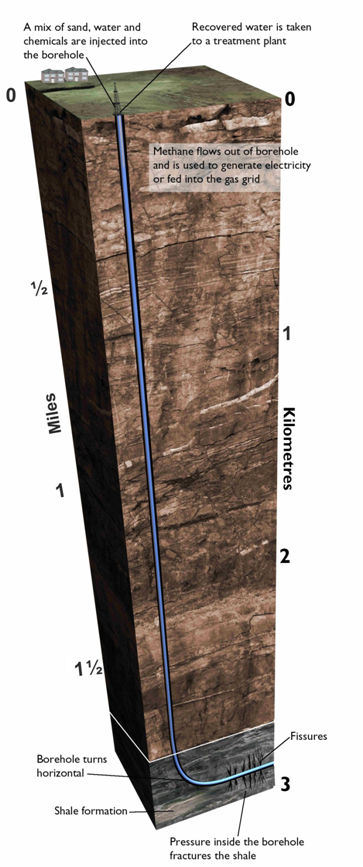

Hydraulic fracturing pretty much ‘does what it says on the tin’. Millions of gallons of water – laced with sand and a chemical cocktail that eases the injection and aids the extraction of the gas – are pumped under very high pressure down vertical wells that a mile or more down swing horizontal to fracture open shale horizons tightly packed with gas, mainly methane. The cracking that liberates the microscopic gas pockets is normally detectable only by sensitive down-hole seismometers, but on rare occasions the surge of fluids under pressure induces seismic slip on pre-stressed faults. For those readers wondering ‘how rare?’ a recent academic review

1 concluded that after hundreds of thousands of hydraulic fracturing operations only three instances of ‘felt’ seismicity had been documented. One of those three instances signaled the start of exploratory gas drilling at Becconsall.

With the ‘Blackpool earthquakes’, fracking – until then more known as a made-up swear word that featured in the cult TV series Battlestar Galactica – became a topic of anxious conversations on Britain’s high streets. A technique that had been used quietly but extensively in UK offshore oil and gas exploration had made landfall. For most people, its sudden appearance under their back yards was most unwelcome.

With the ‘Blackpool earthquakes’, fracking – until then more known as a made-up swear word that featured in the cult TV series Battlestar Galactica – became a topic of anxious conversations on Britain’s high streets. A technique that had been used quietly but extensively in UK offshore oil and gas exploration had made landfall. For most people, its sudden appearance under their back yards was most unwelcome.

Picture - Hydraulic fracturing block column.

Reproduced with the permission of the British Geological Survey © NERC 2011. All rights reserved.

No doubt there is something unsettling about the notion of human actions triggering earthquakes, even a seismic jerk no different to the many mining-related judders that lightly resonate through Britain every year. Shaken and stirred, local protest groups– many featuring the same objectors who oppose wind farms – became organised and concerns spread to other corners of the country where gas drilling was being proposed. A ground tremor that had the shaking intensity equivalent to a classroom of kids jumping up and down was, within week, convulsing communities nationwide.

FRACK NATION

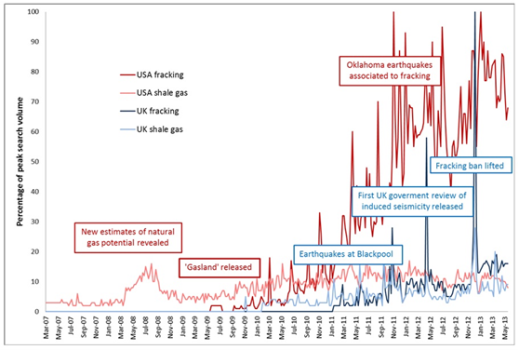

The uncharacteristic ground ructions in rural Lancashire may have been the catalyst for Britain’s anti-frack movement, but the momentum for the spreading unrest came from fracking’s growing infamy on the other side of the Atlantic. In the USA, hydraulic fracturing had for a decade or so been a mainstay of unconventional gas recovery. However, in 2010 it began to gain notoriety courtesy of the award-winning independent film GasLand, which explored the troubling environmental legacy of America’s dash for domestic gas. (Frack Nation, a documentary film countering environmental criticisms of shale gas industry, was released this year.)

In GasLand, dramatic footage of contaminated water wells and flaming kitchen taps presented apparent evidence of the serious side-effects of the violent injection of fracking fluids. The following year, the mainstream movie The Promised Land would augment these environmental woes with Hollywood’s vision of the dramatic social and economic transformations that fracking brings to small town communities in rural America.

Picture: Tracking rising public interest in hydraulic fracturing in the UK (blue) and US (red) as measured in Google searches for ‘fracking’ and ‘shale gas’ using Google Trends

Picture: Tracking rising public interest in hydraulic fracturing in the UK (blue) and US (red) as measured in Google searches for ‘fracking’ and ‘shale gas’ using Google Trends

Certainly, few in the USA would contest the extraordinary transformative capacity of shale gas. According to a 2011 report by the US Department of Energy

2: “…production from shale formations has gone from a negligible amount just a few years ago to being almost 30% of total U.S. natural gas production”. This has brought lower prices, domestic jobs, and the prospect of enhanced national security due to the potential of substantial production growth. But the growth has also brought questions about whether both current and future production can be done in an environmentally sound fashion that meets the needs of public trust.” That ambiguity in what fracking offers – both economic opportunity and environmental threats – is what makes shale gas such a divisive societal issue.

Communities caught up in the US natural gas-drilling phenomenon recognise both positive and negative. In three decades, convoys of 18 wheeler drilling rigs, water trucks and chemical containers have swept from the oily flats of Texas and Louisiana, through the coal lands of Pennsylvania and into the fossil fuel wilds of North Dakota, leaving in their wake a trail of small towns that have tales to tell about the good, bad and ugly sides of shale gas.

In the Pittsburgh area, where fracking has taken hold in recent years, most residents (seven out of 10) see it as either a significant or moderate economic opportunity for the region

3. Although only one in four residents opposed the practice, more than half (55%) believed drilling in Pennsylvania’s gas-rich Marcellus Shale was either a significant or moderate ecological and public health threat. In those areas that have had a longer intimacy with the practice, a more nuanced appraisal emerges of precisely how and why communities are transformed by fracking.

WINNERS & LOSERS

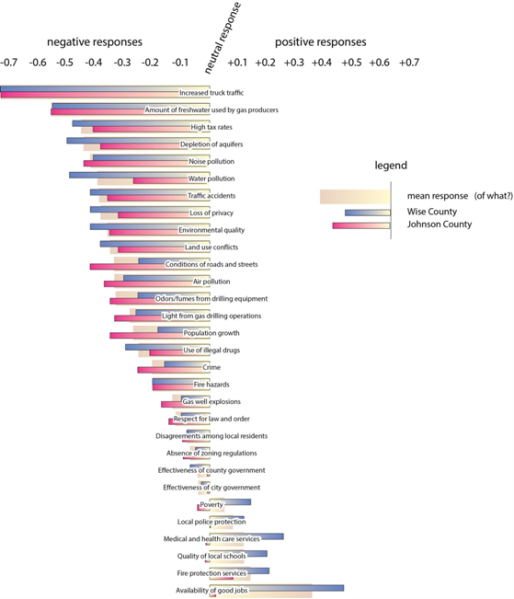

The Barnett Shale region of Texas is the original heartland of US hydraulic fracturing, and so is an area where the complex public reactions to it can be explored in some detail4, 5. They reveal that whether natural gas drilling is seen as good or bad depends to a large extent on whom you ask. Ask those who work in the industry (or have friends or family who do), or receive royalty cheques from the gas sucked from deep beneath their property, or who enjoy long-term residency, and their views are generally supportive. Also an issue is the residency of the gas industry itself.

Picture: Perceived problematic issues associated with natural gas development (after Theodori, 2009).

Picture: Perceived problematic issues associated with natural gas development (after Theodori, 2009).

In counties where natural gas drilling is fairly well established, residents exhibit somewhat more negative perceptions. Residents in those more ‘mature’ counties are more likely to believe that drilling and production wells are too close to homes and businesses, that the gas industry is too politically powerful and that it is uncaring towards the natural environment. They are also the more pessimistic about whether gas development will result in residents’ being better off in the long term.

The message that comes across is that there are winners and losers when the shale gas circus comes to town. The winners are the direct beneficiaries of economic rejuvenation through job creation, increased business activity or higher tax revenues. Direct fracking jobs go to specialist out-of-state workers; but local companies involved in construction, trucking, restaurants, bars, hotels and fuel sales all tend to benefit and a multiplier effect permeates into indirect businesses selling household goods and cars. With increased tax revenues may come improved medical and health services, local schools, and fire protection services.

But what about the losers? A very different tale emerges from some fracked communities. Residents generally lament the increasing traffic, rising damage to roads, diminishing air and noise quality and rapid changes in land use. An influx of workers into quiet farming towns swells coffers but often stretches meagre social services and infrastructure - especially housing. House prices and rental rates soar, squeezing some local residents out of the market.

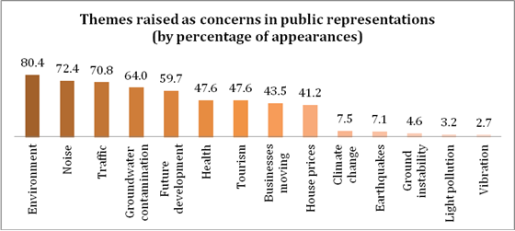

Picture: Themes raised as concerns in public representations (by percentage of appearances).

Picture: Themes raised as concerns in public representations (by percentage of appearances).

Tensions may then arise between locals and incomers; social cohesion can falter, and a community’s sense of place and character can change irrevocably. For those people who are decoupled from the gas bonanza there can be reduction in quality of life, deterioration in mental and physical health, and rising concern over social afflictions like crime and drug abuse.

Alongside potential social disruption and disintegration, there is the threat of environmental and public health costs. Media reports and the Internet abound with apparent cases of water contamination; though many remain legally contested or have ended up in settled compensation claims that essentially prevent details from emerging later. Independent academic studies are hampered by a lack of pre-fracking baseline data on health and water quality, and by the complexities of groundwater behaviour. The limited scientific studies that have been published appear – or can be made to appear - to give succour to both camps.

METHANE

Isotopic analyses of water chemistry in the Marcellus shale gas plays published by researchers at Duke University suggest that methane-infused waters may indeed have come to surface from the deep Marcellus shale layer two miles underground6, 7. They found measurable amounts of methane in 85% of water samples and noted that levels were substantially higher in wells located close to a natural gas well. The big question is - how is the gas getting to the surface?

Picture: Breakdown of percentage of themes by location of planning applications

Picture: Breakdown of percentage of themes by location of planning applications

Interviewed for a recent BBC Horizon documentary, head of the research team Rob Jackson thinks the most likely way that the gas is getting out is by leakage from the wells. “By drilling it straight into the ground, by not sealing it properly with cement, or by using steel tubing where the joints are sealed…it’s actually leaking out the well itself” he says. Far less likely is the sort of direct connection that most people fear – along natural and induced fractures in the rock from the fracked rock, thousands of feet below. Crucially, in none of the thousands of water samples analysed did Jackson’s research team find any chemical trace of fracking fluid.

UK FRACKING

Picture: The high-tech paraphernalia of modern hydraulic fracturing mean that once the initial drilling is complete, an armoury of water pumps provide the high-pressure punch to frack shale horizons a couple of miles down

Picture: The high-tech paraphernalia of modern hydraulic fracturing mean that once the initial drilling is complete, an armoury of water pumps provide the high-pressure punch to frack shale horizons a couple of miles down

With a close eye on the US experience, the scientific and engineering consensus in the UK broadly contends that environmental and health effects of onshore natural gas extraction are a technical issue relating to shoddy well construction at the surface, not with hydraulic fracturing deep underground8, 9. On the wider political front, however, the shale gas debate currently pits arguments of national energy security and economic vitality10 against those of our long-term climate control targets11, 12. Indications are that the British public at large now increasingly sees shale gas as a discussion about energy and climate change13.

But at the sharp end of the UK debate – amid English shires or on Welsh coastal plains where fracking is actually being proposed – there emerges a different public rhetoric. Even as the modest seismic shudder went through Blackpool, planning applications for exploratory drilling with hydraulic fracturing were being considered by other local councils.

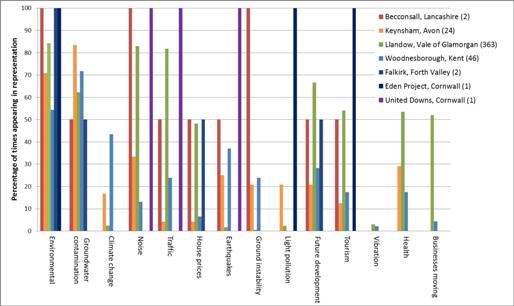

Following the 2010 planning approval at Becconsall, submissions for shale-gas fracking were made for Llandow (Vale of Glamorgan) and, in association with coal-bed methane extraction, for Woodnesborough (Kent), Falkirk (central Scotland) and Keynsham (Avon); applications envisaging fracking to enhance permeability and connectivity for geothermal projects were also proposed for United Downs and the Eden Project in Cornwall. Letters written in response to these various planning applications by members of the public indicate a deep concern about the legacy that residents will be left with when gas is extracted from deep beneath their homes.

The predominant reason for homegrown local objection (~80% overall) – and the only one common to all applications – was classed as ‘environmental’. In many letters this was expressed as a concern about how the local area would be perceived while work was taking place, and about the need to be sensitive of the existing landscape (in one case even to the extent of requesting that the drilling rig be painted an appropriate colour). Protection of specific wildlife and ecological sectors was highlighted, which in the Keynsham objections included concerns for tree protection orders and a bat hibernatorium.

Picture: Public reaction to fracking depends - hardly surprisingly - on who benefits and who doesn't.

Picture: Public reaction to fracking depends - hardly surprisingly - on who benefits and who doesn't.

The next most common objection was ‘noise’, most specifically the vibrations of the drilling rig itself, which was feared to be too disruptive amid the perceived rural idyll of many of the proposed sites. Also prominent in people’s concerns was ‘traffic’ – either increased flow generally in the area or specific disruption from construction and operation of the site. A fourth theme was that of ‘groundwater contamination’, an issue raised more than any other in the Keynsham application for coal-bed methane extraction (83%), yet of little or no concern at the two geothermal projects. A fifth issue was that of ‘future development’, framed mostly as a concern about the ramifications of increased local industrial activity if drilling proved successful. This worry was voiced more frequently in the more recently-submitted applications, perhaps because public awareness was growing of the potential economic ‘bonanza’ of unconventional gas extraction.

A GEOLOGICAL ISSUE?

By and large, the concerns raised by UK residents to the possibility of hydraulic fracturing in their backyard are similar to those that have gained wider recognition in the US. However, there are some homegrown concerns which are less resonant with the American experience.

Anxiety over seismicity and ground instability are rarely mentioned in fracked communities in the US. Over here they feature in many local objections, though they rank low (11th and 12th in importance). Intriguingly, the fear of ‘earthquakes’ or ‘tremors’ was raised once in the case of Becconsall a year before the 2011 ‘seismic storm’ but was more prominent in written objections afterwards, notably at Keynsham (29%) and Woodnesborough (37%). Concerns over ground instability included issues like degradation of the well structure over time and collapse of relict mining or borehole workings, as well as vague or unfocused worries about the unpredictable nature of the geological subsurface.

Despite some apprehension about the deep subsurface aspects of shale gas extraction, most local reluctance over fracking shares the same environmental concerns as that in the USA. These are preoccupations about the surface legacy of gas drilling and the possible blight that its development will bring to rural communities. The environmental concerns raised by vexed residents in the UK may be legitimate reflections on the US experience, but the broader environmental stewardship context is very different. In the USA environmental regulations were especially lax, since fracking companies were specifically exempted from the Clean Water Act. In the UK, a far more stringent set of environmental protocols are already in place14.

PROPRIETARY

Of course important issues do pertain to the subsurface. One of them is who owns the oil and gas down there. In the USA, homeowners can enjoy proprietary rights to hydrocarbon reserves beneath their property. In the UK, landowners may have dominion ‘from the centre of the Earth to the heavens above’ (in Scots law,

‘a coelo ad centrum’); but it is Her Majesty who has the exclusive right of searching, boring for and getting, petroleum. Lovely images though that idea may conjure up, the implication is that private landowners in the UK stand to gain relatively little profit from leasing surface and subsurface access to the hydrocarbons below. The bulk of any shale gas bonanza is currently earmarked for the Crown.

The deep subsurface may be where the geological focus is, but for the concerned public their attention is much closer to home. On both sides of the Atlantic, the primary reasons why people distrust fracking are not geological. Rather, they relate to legal, economic, political, social, environmental and cultural factors. In that sense, fracking is not really a geological issue at all. And yet, of course it is. For the key question that will make or break Britain’s whole ‘dash for gas’ vision is how much of the stuff is actually down there?

* This feature article arises from the BBC Horizon documentary Fracking: the new energy rush, presented by Iain Stewart and last broadcast on 20 June 2013.

References

- Davies, R, Foulger, G, Bindley, A & Styles, P 2013. Induced Seismicity and Hydraulic Fracturing for the Recovery of Hydrocarbons. Marine and Petroleum Geology.

- Shale Gas Subcommittee, US Secretary of Energy Advisory Board, 2011: The SEAB Shale Gas Production Subcommittee Ninety-Day Report – August 11, 2011. Available at: www.shalegas.energy.gov/resources/081111_90_day_report.pdf.

- The Pittsburgh Regional Quality of Life Survey. University of Pittsburgh, University Centre for Social and Urban Research. Available at: www.ucsur.pitt.edu/files/frp/qol/Pittsburgh%20Regional%20QOL%20Survey%20Full%20Report.pdf

- Theodori, 2009. Paradoxical perception of problems associated with unconventional natural gas development. Southern Rural Sociology, 24, 97-117.

- Theodori, G.L. 2012. Public perception of the natural gas industry: data from the Barnett Shale. Energy Sources, part B., 7, 275-281.

- Stephen G Osborn, S G, Vengosh, A, Warner, N R & Robert B Jackson, 2011. Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing. PNAS, 108, 8172-8176. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.110068210

- Nathaniel R Warner, N R, Jackson, R B, Darrah, T H, Osborn, S G Down, A, Zhao, K White, A, & Vengosh, A 2012. Geochemical evidence for possible natural migration of Marcellus Formation brine to shallow aquifers in Pennsylvania. PNAS, 109, 11961–11966. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1121181109

- Royal Society & Royal Academy of Engineering, 2012. Shale gas extraction in the UK: a review of hydraulic fracturing. London: The Royal Society and The Royal Academy of Engineering. Available at: www.royalsociety.org/uploadedFiles/Royal_Society_Content/policy/projects/shale-gas/2012-06-28-Shale-gas.pdf

- Geological Society of London, Briefing Note on Shale Gas www.geolsoc.org.uk/shalegas

- Institute of Directors 2013. Britain’s Shale Gas Potential.

- Bassi, S, Rydge, J, Khor, C S, Fankhauser, S, Hirst & Ward, B 2013. A UK ‘dash’ for smart gas. Grantham Institute Policy Brief.

- Broderick J, et al.: 2011, Shale gas: an updated assessment of environmental and climate change impacts. A report commissioned by The Co-operative and undertaken by researchers at the Tyndall Centre, University of Manchester

- O’Hara, S, Humphrey, M Jaspal, R, Nerlich, B, & Poberezhskaya, M 2013. Public perception of shale gas in the UK: how people’s views are changing. University of Nottingham. Available at: www.groundgassolutions.co.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2013/03/Nottm_PublicPerceptionsShaleGasUK_Mar2013.pdf

- Environment Agency Guidance Note: Regulation of exploratory shale gas explorations. www.groundwateruk.org/downloads/EA_ShaleGasRegulation.pdf