Morgan, N., Rock bands. Geoscientist 30 (6), 27, 2020

https://doi.org/doi: 10.1144/geosci2020-095, Download the pdf here

Geologist, science writer and music lover Nina Morgan relishes the sounds of stones

From early times, stone workers have tested blocks of stone with a sharp tap, listening for ringing sounds to check for cracks or flaws. Geologists, too, often take advantage of this trick to map subtle changes in lithology, porosity and permeability in the field. But these days even the most avant garde Hard Rock bands don't seem to look to geology to create their sounds. Perhaps they're missing a trick.

From early times, stone workers have tested blocks of stone with a sharp tap, listening for ringing sounds to check for cracks or flaws. Geologists, too, often take advantage of this trick to map subtle changes in lithology, porosity and permeability in the field. But these days even the most avant garde Hard Rock bands don't seem to look to geology to create their sounds. Perhaps they're missing a trick.

The musical properties of rocks have been exploited from ancient times in many parts of the world. But arguably it was a stonemason Joseph Richardson [1790 – 1855], born in Keswick, Cumbria, who brought the musical possibilities of stones to international attention in the form of a lithophone – a xylophone made up of tuned stone keys. He named his creation the 'Richardson and Sons Rock, Bell and Steel Band'.

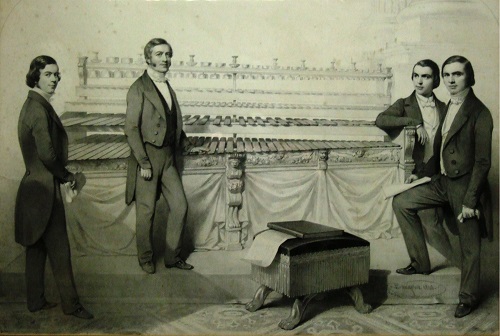

Left: Joseph Richardson & sons (Keswick Museum)

Early inspiration

Richardson must have been inspired to build his lithophone by tales of the musical stones around Skiddaw collected by Peter Crosthwaite [1735-1808], founder of the Keswick Museum. In 1785, Crosthwaite recorded the discovery of his '6 first music stones at the Tip end or North end of long tongue'. The stones, composed of a coarse-grained hornfels created when the Ordovician mudstones and siltstones of the Skiddaw group were affected by low-grade regional metamorphisim and deformation associated with the Acadian Orogeny in the Devonian, were, he claimed, in perfect tune. The discovery inspired him to shape more stones to produce other notes to create a set of Musical Stones.

Later the musically inclined Richardson further explored the sound properties of Lake District rocks. In 1827, while building houses at Thornthwaite, he struck musical gold with the hornfels around Skiddaw, and started work to create a lithophone capable of playing every musical note. Finding, testing and shaping suitable stones to assemble into an instrument took nearly 13 years, and nearly drove his family into poverty.

In 1840 Richardson enlisted the help of his three sons to play his new lithophone. They built up an impressive repertoire, including selections from Handel, Beethoven, Mozart and arrangements of waltzes, quadrilles, gallops and polkas. Their concerts were very popular and received rave reviews. "The richness as well as the sweetness of the tones produced seemed to excite the astonishment of all who heard them" noted one commentator.

In the mid-1840s Richardson updated the instrument, adding octaves of steel bars, Swiss bells, drums and various percussion instruments, and the group became known as the Richardson & Sons, Rock, Bell and Steel band. They gave over sixty concerts in London, toured all over Britain, performed in France, Germany and Italy and on 23 February 1848 played at Buckingham Palace by command of Queen Victoria. But their career was cut short by the death of their star player shortly before they were due to leave for a tour in America. The mighty instrument was packed away, and eventually given to the Keswick Museum in 1917, where it is still on display.

New Music

Although other performers on Musical Stones followed during the 19th century, including the Till Family Rock Band, who played at the Crystal Palace in 1881 and toured in America, all went quiet on the lithophone front for many years. But now, interest in musical stones seems to be growing. A team of musicians, scientists and geologists at the University of Leeds have created a 21st century version with each stone wired up to a battery of computers to create a wider range of musical sounds. The percussionist Evelyn Glennie gave the updated instrument its premier outing in 2010.

It was an impressive performance. But so far, the new lithophone doesn't seem to have taken off. Perhaps the fact that it weighs 100 kg has something to do with it.

End notes: Sources for this vignette include: Julian WS Litten and Jamie Barnes, Richardson & Sons Rock, Bell & Steel Band, Magazine of the Friends of Kensal Green Cemetery, March 2006, pp 4-6; The Musical Stones of Skiddaw, published online by Allerdale Borough Council and the Keswick Museum; Martin Wainwright, Evelyn Glennie's Stone xylophone, The Guardian 18 August 2010; the website https://ruskinrocks.leeds.ac.uk/, includes a demonstration of the modern version of musical stones being played.

Nina Morgan is a geologist and science writer based near Oxford. Her latest book, The Geology of Oxford Gravestones, is available via www.gravestonegeology.uk