Laurance Donnelly and Alastair Ruffell tell how the Specialist Group originated and has developed since its early days.

.jpg?h=150&w=305&la=en) The Forensic Geoscience Group (FGG), is the newest of the Geological Society’s 23 Specialist Groups and Joint Associations (a number destined, perhaps to go down by up to two). It was established in December 2006 by Dr Laurance Donnelly, who served as its first Chair (2006-2011). Dr Alastair Ruffell served as the second chair (2011-2016). The post is currently held by Dr Jamie Pringle (2016). This article provides a personal account documenting the establishment of FGG and some of its main achievements.

The Forensic Geoscience Group (FGG), is the newest of the Geological Society’s 23 Specialist Groups and Joint Associations (a number destined, perhaps to go down by up to two). It was established in December 2006 by Dr Laurance Donnelly, who served as its first Chair (2006-2011). Dr Alastair Ruffell served as the second chair (2011-2016). The post is currently held by Dr Jamie Pringle (2016). This article provides a personal account documenting the establishment of FGG and some of its main achievements.

Historical Overview

Forensic geology is by no means new. According to legend, an examination of soil and rock fragments found in horses’ hooves assisted Roman soldiers in locating the camp of the enemy. The documented application of geology to assist with a police investigations dates back to the middle part of the 19th Century.

Professor Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (1795–1876), a German scientist working in Berlin, was able to assist police and identify the provenance of sand that had been used to substitute for stolen silver being transported in wooden barrels on a train in Prussia. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the (fictitious) work of his violin-playing, coke sniffing hero Sherlock Holmes (1887-1927), made reference to the idea that geology (soil analysis) could help investigate crime. The colour and consistency of splashes of mud on a pair of trousers helped Holmes to identify the parts of London through which a visitor to 221B Baker Street had walked.

Professor Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (1795–1876), a German scientist working in Berlin, was able to assist police and identify the provenance of sand that had been used to substitute for stolen silver being transported in wooden barrels on a train in Prussia. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the (fictitious) work of his violin-playing, coke sniffing hero Sherlock Holmes (1887-1927), made reference to the idea that geology (soil analysis) could help investigate crime. The colour and consistency of splashes of mud on a pair of trousers helped Holmes to identify the parts of London through which a visitor to 221B Baker Street had walked.

Hans Gustav Adolf Gross (1847-1915) was an Austrian examining magistrate and professor of criminology. In 1893 he published, ‘Handbuch für Untersuchungsrichter, Polizeibeamte, Gendarmen’ (Handbook for Magistrates, Police Officials & Military Policemen). He noted that: “Dirt on shoes can often tell us more about where the wearer of those shoes had last been than toilsome inquiries”.

George Popp (1847-1915), working in Germany in 1904 on the murder of Eva Disch (who had been strangled with her own scarf) analysed nasal mucus on a handkerchief found at a crime scene. Fragments of coal, snuff, and hornblende crystals were consistent with materials found beneath the fingernails of a suspect. Popp subsequently investigated other murders using microscopic analysis (the Margaret Filbert murder, Bavaria 1908) and he noted how the stratigraphic layering of different soils on shoes could be used to build a profile of an offender’s movements, placing him at a scene of crime. These cases were based on the principle formulated by the forensic scientist, Edmund Locard (1877-1966). He developed the concept that “every contact leaves a trace” - ‘Locard's Exchange Principle’.

In 1936, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) first applied soil analysis to a case (The Matson Kidnapping) to identify where a victim had been prior to his murder. The investigation of the Green River Murders in the mid-1980s also used evidence from microscopy - a serial killer was convicted of 48 murders and later confessed to dozens more. Murray & Tedrow published ‘Forensic Geology’ in 1975, the first textbook to combine geology with operational cases.

In 1936, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) first applied soil analysis to a case (The Matson Kidnapping) to identify where a victim had been prior to his murder. The investigation of the Green River Murders in the mid-1980s also used evidence from microscopy - a serial killer was convicted of 48 murders and later confessed to dozens more. Murray & Tedrow published ‘Forensic Geology’ in 1975, the first textbook to combine geology with operational cases.

Picture: A forensic geologist may be called to provide support for a crime scene examination (Photo: © Laurance Donnelly)

In the UK, during the 1970s and 1980s, the Home Office Central Research Establishment at Aldermaston made advances in areas such as soil density-gradient examination techniques, cathodoluminescence, colour analyses and particle-size analysis. The Forensic Science Services (FSS - now closed) was set up in the early part of the 21st Century as the Natural Justice Group, and included forensic soil-science services to police forces and Government departments.

Renaissance

In 1994, Dr Donnelly began searching Saddleworth Moor, in the Pennines, for the last remaining victim of the Moors Murders (ongoing). He used geological methods and strategies not conventionally used by Police. Up until this time, most police searches followed a counter-terrorism strategy, using fingertip line searches, some metal detectors and search (cadaver) dogs. This reflected the police training received from the military following the Irish Republican Army’s unsuccessful attempt to assassinate the Prime Minster, Margaret Thatcher in 1984 (by planting a time-delayed bomb in the Grand Hotel, Brighton). These types of police and military led ground searches rarely considered a detailed evaluation of the geology.

By the early 2000s it became apparent to Donnelly that even though police and law enforcement are not conventionally trained in geology – any more than geologists are familiar with police and crime-scene protocols - there were clear benefits to including geologists in certain types of criminal investigation in the UK and globally. This included searches in Northern Ireland for the ‘Disappeared’ associated with the IRA, being conducted by Ruffell, and (very successfully) by the Independent Commission for the Location and Identification of Victims’ Remains.

By the early 2000s it became apparent to Donnelly that even though police and law enforcement are not conventionally trained in geology – any more than geologists are familiar with police and crime-scene protocols - there were clear benefits to including geologists in certain types of criminal investigation in the UK and globally. This included searches in Northern Ireland for the ‘Disappeared’ associated with the IRA, being conducted by Ruffell, and (very successfully) by the Independent Commission for the Location and Identification of Victims’ Remains.

Picture: Forensic geology search (Photo © Laurance Donnelly)

Geologists supporting the police usually worked in isolation, and fellow geologists were largely unknown to eachother as they often tended to work covertly on sensitive, high-profile cases. There was, for example: no collaboration between geologists; no opportunities to discuss casework or research; no sharing of knowledge information or ideas; no encouragement to publish papers, guidance or protocols; no opportunities for career development; no incentives for the advancement of ‘forensic geology’ and no formal professional representation for geologists working in the field of forensic science, policing and law enforcement. This was about to change.

On 12 March 2002, a presentation entitled, ‘How Forensic Geology Helps Solve Crime: Forensic Geology and The Moors Murders’, was delivered by Donnelly to the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Earth Science, at Westminster Palace, House of Commons, in London. This drew attention to the applications of geology to police casework, and was followed by an invitation to Donnelly to discuss forensic geology on BBC Radio 4’s ‘Material World’. These events attracted interest in forensic geology from other geologists, forensic scientists, police officers, politicians and the media. In 2002, Donnelly began formulating a plan to develop a professional group on the subject. But where was this group to be focused?

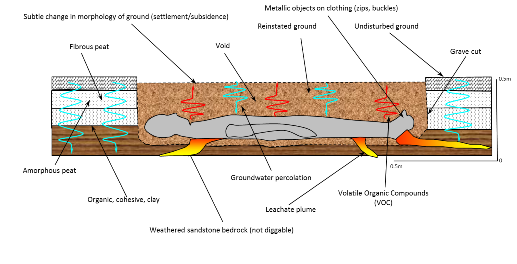

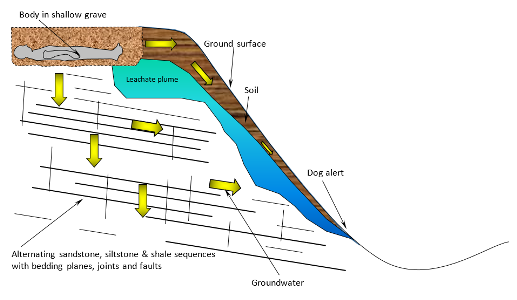

Diagrams, left and below, right:Conceptual geological model and hydrogeological model for a grave (Source: © Laurance Donnelly)

Diagrams, left and below, right:Conceptual geological model and hydrogeological model for a grave (Source: © Laurance Donnelly)

In 2003, a forensic geoscience meeting was held at the Geological Society of London (GSL – see Pye & Croft, 2004). In the ame year, the Centre for Australian Forensic Soil Science (CAFSS) became established after the successful application of forensic geology using largely polarising microscope and X-Ray Diffraction. In 2011 the Centre became a ‘Forensic Science Centre of Specialisation’, approved by Australia-New Zealand Policing Advisory Agency. Later, in Scotland, came the development of a Geoforensic GIS tool (SoilFit) and Geoforensics and Information Management for Crime Investigation (GIMI), to develop new technologies in the forensic investigations of crime scenes.

Establishment of FGG

Following over three years of planning and gathering support, in December 2005 Donnelly presented a proposal to GSL for a new specialist group on Forensic Geology. Approval was subsequently given by Council on 22 November 2006, for a ‘Forensic Geoscience Group (FGG)’.

Following over three years of planning and gathering support, in December 2005 Donnelly presented a proposal to GSL for a new specialist group on Forensic Geology. Approval was subsequently given by Council on 22 November 2006, for a ‘Forensic Geoscience Group (FGG)’.

FGG’s inaugural meeting took place at Burlington House on 18 December 2006, in time for the Society’s Bicentennial in 2007. This establishment of FGG was supported by the then UK Police National Search Adviser, Commander Mark Harrison, MBE (now with the Australian Federal Police), who was working with Donnelly on Saddleworth Moor at this time. Mark subsequently commented (Police Professional, September 25, 2008, 20-22): ‘Forensic geology can bring significant benefits to policing. Geologists’ focus on exploration fits very well into a police and forensic environment during a criminal investigation. The expertise of a geologist would be of assistance when working anywhere in the world’.

The objective of FGG is to advance the study and understanding of forensic geoscience (also known as ‘forensic geology’ and ‘geoforensics’) - ‘the application of geology to policing, law enforcement and criminal investigations’. Forensic geology may also assist with humanitarian, environmental, engineering and geotechnical investigations that may become subject to legal enquiry. Forensic geologists have also been involved in fakery and fraud cases including: minerals and mining scams (e.g. Bre-X, 1987) rare fossil sales, diamonds, gemstones and Rare Earth metal investments and the mineralogical analysis of paint to reveal art forgeries. A forensic geologist may be invited by the police or a law enforcement agent to assist with certain types of criminal activity relating to homicide, terrorism or organised crime.

Events & publications

From 2006-2016 at least 227 forensic geology events have been held throughout the world. At least seven books have now been published, two GSL Special Publications, and numerous peer-reviewed papers, conference proceedings, and newspaper and magazine articles. Members of FGG have been involved with many of these events and as authors, co-authors, contributors, advisors, editors or peer reviewers. ‘A Guide to Forensic Geology’ is currently being written.

From 2006-2016 at least 227 forensic geology events have been held throughout the world. At least seven books have now been published, two GSL Special Publications, and numerous peer-reviewed papers, conference proceedings, and newspaper and magazine articles. Members of FGG have been involved with many of these events and as authors, co-authors, contributors, advisors, editors or peer reviewers. ‘A Guide to Forensic Geology’ is currently being written.

Picture: Mock crime scene, 2013 - during an International Schools Science Fair, Cornwall.

Forensic geology has also brought together many of the Society’s Specialist and Regional Groups. Numerous joint projects and collaborations have taken place with a host of commercial companies, police forces, forensic scientists, law enforcement agencies, other co-professional bodies, universities, research institutes, the media and school children.

FGG also developed the Geoforensic International Network (GIN), which brings together forensic geologists, geoscientists, police, law enforcement officers from approximately 40 countries interested in developing and promoting forensic geology.

IUGS

In 2008, following the success of FGG, Donnelly was invited by International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) to set up an International Working Group on Forensic Geology. This was established in Uruguay and Namibia as part of the IUGS Commission on Geoscience for Environmental Management (GEM). The first Ibero-Latin American course on Forensic Geology was held in Colombia in 2009 with the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forense and the Federal Police in Bogota, Colombia. In 2011, IUGS promoted the Forensic Geology Working Group to the IUGS Initiative on Forensic Geology (IFG) (ongoing).

In 2008, following the success of FGG, Donnelly was invited by International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) to set up an International Working Group on Forensic Geology. This was established in Uruguay and Namibia as part of the IUGS Commission on Geoscience for Environmental Management (GEM). The first Ibero-Latin American course on Forensic Geology was held in Colombia in 2009 with the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forense and the Federal Police in Bogota, Colombia. In 2011, IUGS promoted the Forensic Geology Working Group to the IUGS Initiative on Forensic Geology (IFG) (ongoing).

Picture: IFG at Burlington House, London. Working Group to the IUGS Initiative on Forensic Geology.

Training

FGG and IUGS-IFG have been invited to provide formal knowledge-exchange, capacity building, and training for geologists, police, law enforcement, forensic scientists and lawyers in many parts of the world - including the UK Police National Crime Agency (formerly the National Police Improvements Agency (NPIA) and Serious Organised Crime Agency (SOCA)); Russian Federal Centre of Forensic Science (RFCFS) of the Russian Ministry of Justice, in Moscow; Australian Federal Police; Brazilian Federal Police; National Research Institute of Police Science, Japan; the Carabinieri and Polizia (Italy); and the Abu Dhabi Police, Navy and Coastguard.

Teaching, research, outreach

Picture: Geochemical surveys used as part of a search strategy to locate a burial

Picture: Geochemical surveys used as part of a search strategy to locate a burial

FGG has encouraged and endorsed the formal teaching of forensic geology modules on BSc Geology courses (e.g. University of Leicester), MSc (e.g. Università degli Studi di Messina, Dipartimento di Scienze dell'Ambiente, Messina, Sicily) and PhD (e.g. Oxford University, University of Keele, Queen’s University Belfast and both Birkbeck College and University College London). Research has also been undertaken at The Body Farm, in Knoxville, Tennessee, to understand the generation and migration of leachate and volatile organic compounds and how this can influence searches for homicide graves. FGG has supported a new human decomposition facility; the Australian Facility for Taphonomic Experimental Research (AFTER).

Forensic geology has captured the imagination of schoolchildren and university students. Numerous events have been held across the UK and globally for those aged 5-18. For instance, a mock crime-scene was established at the 2013 International School Science Fair, held in Cornwall. Following a series of lectures the children were able to conduct ground searches for (fake!) nail-bombs and weapons. Dressed in crime-scene protective suits they collected samples from a vehicle, spade and clothing and the analysis of these soils provided geological evidence and helped them to solve a fabricated crime. Forensic geology has been actively pursued by the media as this seems to have seized the public’s interest, and many public lectures have been delivered.

Operational support

FGG was not set up only to support the UK Police. However, FGG committee members have been invited to enlist on the UK Police National Crime Agency, Expert Database as ‘Forensic Geologists’. As such, geologists have provided advice, guidance, soil analysis and ground searches for numerous cases. Many of these were high profile, attracting national and international media interest.

FGG was not set up only to support the UK Police. However, FGG committee members have been invited to enlist on the UK Police National Crime Agency, Expert Database as ‘Forensic Geologists’. As such, geologists have provided advice, guidance, soil analysis and ground searches for numerous cases. Many of these were high profile, attracting national and international media interest.

Picture: Dealing with media attention is one of the new sckills that must be learnt by a Forensic Geoscientist.

Today, major crime laboratories throughout the world, public and private, conduct crime-scene investigation, including the analyses of soils and geological materials. Geologists are required to assist the police at crime scenes to collect and evaluate samples. Geological trace evidence involves analysis, interpretation, presentation and explanation of geological evidence, at a scene of crime, or from an item or object, as intelligence and as evidence.

This includes: rock fragments, natural soils and sediments, artificial (anthropogenic) man-made materials derived from geological raw materials (bricks, concrete, glass or plasterboard etc.) or microfossils. Trace evidence may be transferred onto the body, person or clothing of a victim or offender, or onto vehicles or objects from and to a crime scene. This, when interpreted by an experienced forensic geologist can help with crime reconstruction and may be admissible as physical evidence in a court.

Forensic geologists are now routinely called upon for ground searches, applying techniques adopted from mineral exploration and geotechnical ground investigations. Such searches can be designed and implemented so as to locate homicide graves, mass graves related to genocide, weapons, firearms, improvised devices, explosives, drugs and items of value (e.g. stolen items, money, coinage, jewellery).

Ground searches may take place in urban, rural or remote locations, on land or in water (e.g. canals, rivers, lakes, reservoirs and the sea). A search may be conducted to: obtain evidence for prosecution, gain intelligence, deprive criminals of resources and opportunities to commit crime or acts of terror, locate vulnerable persons, protect potential targets and venues, search for homicide graves and associated buried items or objects.

Picture - Forensic geology search. Dealing with sensitive sites demands a high degree of tact and discretion.

Picture - Forensic geology search. Dealing with sensitive sites demands a high degree of tact and discretion.

Due to the sensitive and often high profile nature of crimes being investigated, many cases cannot be published and may only be referred to anonymously. This includes the search for missing persons, or, for example, the detection of a dismembered murder victim in northern England, following geomorphological analysis of air photos. Another victim’s grave was found in a remote location following analysis of sand on a suspect’s vehicle, and by the subsequent deployment of geophysics and a detector-dog survey. A geological search strategy also helped the police locate the grave of a murder victim who went missing well over a decade earlier.

The UK Police National Search Adviser, National Crime Agency, commented: ‘Geology in support of the search for a concealed murder victim is a relatively new and largely overlooked tool in the box’. A Major serving in the, British Army, Royal Engineers, stated: ‘I have been actively involved in the world of search for 27 years and find it staggering that we (the British Army) remain oblivious to the assistance that geologists can deliver to any search task, let alone the strategy associated to it. I believe that a geologist must now be considered a critical asset to any search adviser during the planning phase of any search task’.

Authors

* Dr Laurance Donnelly (pictured, applying geophysical search techniques) , Founder and First Chair, GSL-FGG; Chair, IUGS-Initiative on Forensic Geology (IFG). Arup, 6th Floor, 3 Piccadilly Place, Manchester, M1 3BN E: [email protected] and [email protected]. Dr Alastair Ruffell, Co-founder and Second Chair GSL-FGG; Queens University Belfast, Department of Geography and Archaeology. E: [email protected]

* Dr Laurance Donnelly (pictured, applying geophysical search techniques) , Founder and First Chair, GSL-FGG; Chair, IUGS-Initiative on Forensic Geology (IFG). Arup, 6th Floor, 3 Piccadilly Place, Manchester, M1 3BN E: [email protected] and [email protected]. Dr Alastair Ruffell, Co-founder and Second Chair GSL-FGG; Queens University Belfast, Department of Geography and Archaeology. E: [email protected]

Further reading

- Bergslien, E 2012. An Introduction to forensic Geoscience, 2012, Wiley-Blackwell, 582pp.

- Di Maggio, R M, Matteo Barone, P, Pettinelli, E, Mattei, M, Lauro, S, Banchelli, A 2014. Geologia Forense. Introduzione alle geoscienze applicate alle indagini giudiziarie. Italia.

- Donnelly, L J 2010. The role of geoforensics in policing and law enforcement. Emergency Global Barclay media Limited, January 2010, 19-22.

- Donnelly, L J, & Harrison, M 2015. A Collaborative Methodology for Ground Searches by a Forensic Geologist and Law Enforcement (Police) Officer: Detecting Evidence Related to Homicide, Terrorism and Organized Crime. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Engineering Geophysics, Session on Forensic Geosciences, Al Ain, UAE, FG02, 260-268.

- Donnelly, L J, Pirrie, D, Ruffell, A, Dawson, L (Eds) (2017). A Guide to Forensic Geology. International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS), Initiative on Forensic Geology (IFG). Geological Society of London (pending).

- Murray, R 2011 Evidence from the Earth, 2nd edition, Mountain Press, Missoula, MT, 201pp.

- Murray, R, Tedrow, J, 1975. Forensic Geology. New Brunswick, NJ. Rutgers University Press. 217pp.

- Pirrie, D, Ruffell, A, Dawson, L 2014. Environmental Geoforensics. Geological Society of London Special Publication, 384, pp273.

- Pye, K 2007. Geological and Soil Evidence. CRC Press, 335pp.

- Pye, K, Croft, D 2004. Forensic Geoscience, Principles, Techniques and Applications. Geological Society of London, Special Publicaiton 232, 318pp.

- Ritz, K, Dawson, L., Miller, D. 2009. Criminal and Environmental Forensics. Springer, 519pp.

- Ruffell, A R & McKinley, J 2008. Geoforensics. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, UK.

- www.forensicgeologyinternational.org