In August's issue of Geoscientist, the monthly colour magazine of the Geological Society, Media Monitor examines the importance of biography in understanding and popularizing science

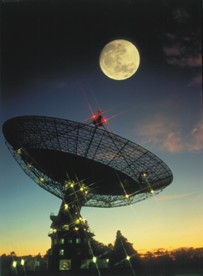

The Parkes Radio Telescope by John Shostak. Photo – CSIRO

Some kind of a threshold passed this year. Now not only do popular science books have a prize of their own, but they are invading the domain of more "mainstream" literary prizes too. Whatever next?

This was why on 23 May, with a picture of Mr Martin Amis looking disagreeable, a piece appeared in the Daily Telegraph under the headline Extinct Sea Creatures keep Amis off shortlist. The creatures in question were trilobites, and the book was Richard Fortey’s Trilobite! Eyewitness to Evolution. The word in the cocktail parties was that Amis’s autobiography Experience had failed to make the Samuel Johnson Prize list because of it.

Mr Amis, whose writing is often described as "combining the fashionable with the unreadable", had been displaced by a book combining the unfashionable with the inedible. But, as Andrew Marr (BBC Political Correspondent and chairman of the Samuel Johnson Prize Committee) remarked: "…our current non-fiction writing is currently eclipsing anything being done in the novel in this country". (Whether Mr Marr regards autobiography as a form of fiction was not revealed, though the way his quote was used rather suggested that he does. He may not be far wrong, of course.)

Richard Fortey has made the melding of science with autobiography something of a trademark, and it is partly the artistry with which he does so that raises his work into the realm of Literature. (I have witnessed the embarrassment into which this suggestion plunges him, and I apologise for making it again. I cannot, though, compete with the well-known publisher Mr Stuart Proffit (then at Harper Collins) who at the launch of Life – an unauthorised biography described Richard as "The Mozart of the fossil". This piece of luvvyspeak would have embarrassed anyone, and deserves to be recorded for posterity.)

However, hyperbole aside, Richard Fortey has led the way in the UK in showing that books of what the French so delightfully call haute vulgarisation need not hang their heads beside other literary forms – at least not when in the hands of scientists who just happen to be real writers. But there is something else, something important, about the use of biography.

Successful extended science writing often involves the counterpoint of science with something else – in Richard’s case, his life and career; in Steve Gould’s, baseball, music, renaissance architecture, you name it. But autobiography is special in that, in addition to leavening the mix, it can also introduce development. Character development is what provides biography and fiction with its inherent interest. Books that lack it betray themselves immediately as the sterile products of manipulative minds, capable of devising plots but blind to the one thing that could give them life. Alas, that does not seem to be a bar to their publication.

Experience, to borrow Amis’s title, teaches us that life changes us; just as – to borrow Gould’s favourite theme – the exigencies of existence on this planet have shaped the history of life in unpredictable and unrepeatable ways. We are the products of contingency on our small scale, just as the history of life is, on its grand scale. One theme enlightens the other.

But autobiography also enlightens the scientist, in ways that accounts of science alone cannot. A time there was when scientists, basking in the public adulation of their perfect works, were happy to seem to embody them; to take on the fictitious mantle of infallibility that the public had not (then) seen through. Scientists need to leave this behind – and undergo a bit of character development of their own. Those days are gone. The image of the impersonal scientist, whose life is somehow not prey to the usual motives that animate ordinary mortals, is finished.

The public is more ready for this than scientists. Over the last 15 years the fact that the public has lost its appetite for cliché in the portrayal of scientists, has become obvious through several major motion pictures. The crucial thing about films is that by their very nature they have to provide characters that are to some extent cliché. This is because there is no time for complex character analysis. The audience must grasp the characters very quickly.

How then do you, as screenwriter, stop your characters looking ridiculous? The answer is to take character traits (that might be cliché on others) and graft them onto those that would not normally display them. Think of the original effect achieved by combining moral emptiness, ruthless brutality and extreme intelligence in the character of Hannibal Lektor.

But – and this is crucial - the process cannot go too far. If the grafted traits (the anti-cliché-devices) are too far from what is believable, the result will not work; the graft will not take. The public will reject the Frankenstein monster the writer has created. This is why it is particularly encouraging that scientists now frequently appear in films as intuitive, empathic, in touch with their feelings, concerned about the Earth, and – most amazing of all – even cool. It is encouraging because the public can swallow the idea.

One who, since Jurassic Park has almost cornered the market in thoughtful and sympathetic scientists is the Australian actor Sam Neill. Neill recently appeared in a small film called The Dish. This gentle comedy tells the story of the Australian radio telescope that provided the TV pictures of the first (Apollo 11) moonwalk.

"Based on a true story", there is no telling how much of the tale is true. But historical accuracy is not what matters here. What matters is that the scientists and engineers portrayed are not only dedicated and excited at being part of a great scientific and technological event. They are also nervous, jealous, frightened of cocking up; they have chips on their shoulders, lie to authority so as not to lose face, make blunders, spend hours fruitlessly going back to first principles to get themselves out of trouble, and then have brilliant flashes of insight that save the day.

Now it is MM's experience that that is rather like life; the life of a scientist or anyone else. Human frailty does not diminish the scientist characters. Why should it? They cope like we all do with unforeseeable random events (power cuts, high winds, losing spacecraft, even bullshitting NASA); they take courageous chances beyond the known safety envelopes; they face their jealousies and inferiority complexes, work them out, and come back stronger. They develop. This is what being a scientist is really like, because it’s like being anything else. The public will respect scientists more for coming clean about it.

By writing about science in the way they are encouraged to do by the conventions of academic writing scientists reinforce a fiction. Academic papers are written so as to conceal mistakes, blind alleys, cock-ups. But when writing for the public, the messiness of the whole process should be allowed to come through.

The public can handle that much reality. The white coat has to come off.

Ted Nield

[Daily Telegraph 23.5.01: Extinct sea creatures keep Amis off shortlist. For moire info about Parkes and Apollo 11, go to http://www.parkes.atnf.csiro.au/]