Many scientists have trouble dealing with the media – and vice versa. Could the trouble lie in contrasting psychologies?

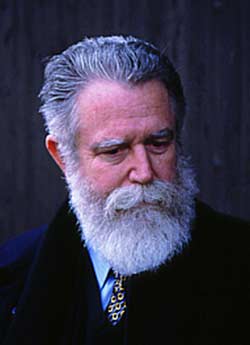

In this month of the eponymous fly, American artist James Turrell will begin a new project – to use his skill in manipulating light to illuminate the Thames – London’s very own Heart of Darkness.

Turrell, one of America’s greatest living artists, is already world famous for his long-term dream of creating an artwork and exhibition space at Roden Crater - a cinder cone in Arizona. His artwork experiments with fleeting effects of light and space - effects that he hopes create a sensation, he says, "like the wordless thought that comes from looking in a fire". Roden Crater, an extinct volcano that he has been transforming into a "celestial observatory" for the past quarter century, is his masterpiece. Not far from the Grand Canyon and the Painted Desert, this "great geologic eye" brings the heavens down to Earth in a series of sky-lit spaces excavated from the volcano’s heart.

Like some modern-day Stonehenge, Roden Observatory – its very name seeming to hint at art/science crossover - has that same sense of nameless significance. It is expected to open to the public next year. What it offers the visitor is the impression of being involved in an artist’s personal quest to define and enhance the relationship of human beings to the universe. And that, of course, is just where the arts and sciences unite – each striving in its own way to define our place in Nature.

Which – as the text for a sermon, would all seem very cosy. However, sitting as he does on the cusp of the arts and the sciences, MM has observed over the years that scientists’ impatience with those who do not share their peculiarly different mind-set often damages their chances of bringing the scientific heavens down to Earth. These rather gloomy thoughts recur most often at such events as the recent Earth System Processes meeting, or the annual BA Festival of Science, when MM’s duties bring him into simultaneous contact with two contrasting companies - namely scientists and media folk.

In what way contrasting? Consider this. Yesterday evening, MM was sitting before his (other) keyboard, blundering through Beethoven’s Sonata Pathétique. He was doing so in the (vain) hope that the harder he worked at it, the more effortless he would come to seem. Effortlessness in execution is the mark of anyone who’s any good in nearly all spheres of human activity. You see the same approach among – to choose at random – actors, pole-vaulters, ice-skaters, poets, soufflé chefs - and science writers. It goes for almost every profession because in one way or another, they are all performing arts.

But science is different. Geneticist and science commentator Professor Steve Jones has written that science is the most – and maybe the only – "democratic" field of endeavour, wherein - with diligence and application - any intelligent person can make a genuine and worthwhile contribution to the whole. Science is a group effort, a massive common undertaking, like some great termite nest. The joy of this is that you can be a mediocre scientist and still be useful. Alas, nobody has any use for a mediocre poet or a third-rate Beethoven interpreter.

Alongside science’s democratic spirit and its collective amassing of information comes a stolid work ethic that makes effortlessness seem almost a sin, and turns ephemerality into an insult. And thus at every conference with a media presence one encounters scientists who, faced with the surprisingly hard graft required to get coverage for even the most newsworthy stories, quickly become demoralised. "The trouble with this PR game is that it all has to be done again tomorrow" is a common complaint - once made to me by a former President of this Society.

Think how odd it would be to hear an actor complaining after a matinée: "Oh, the trouble with this acting game is that it all has to be done again in the evening". When scientists work hard, they want something permanent to show for it. A monograph on the Ordovician Inarticulata will stand as a joy forever. The comic cuts, by contrast, really don’t seem worth the candle.

Some years ago the BA Festival became the launch pad for a new Natural History Museum booklet entitled Amber: the natural time capsule. Media coverage focused on the poignant case of a Mexican mayfly, which had become enmeshed in resin one Tuesday afternoon, 25 million years ago. It had but a few hours to live; but it lived even more briefly - and was preserved forever. The public loved the story, which left them with fleeting bits of knowledge and a strong, lasting sensation that science can be touching and fascinating.

Those who read that story will by now have forgotten Mexico, 25 million years – and, probably, the mayfly. But they will remember the pleasurable experience – just as an audience remembers the atmosphere of Cat on a hot tin roof but not the dialogue.

The newspaper science writer, his mayfly copy filed, will have ended his day satisfied that he had told a good tale and conveyed a vivid sensation. The NHM’s Media relations folk will have woken up to next day’s newspapers and been happy, because people were being left with favourable feelings about science and, maybe, the NHM. But I can see how some of the scientists may have slumped into their armchairs that evening feeling that a day had been spent with nothing to show for it - and wondering why they bothered.

But - never mind. They, after all, could return to their back rooms in South Ken, and - long after the public’s eye had moved on – take the mayfly, study it exhaustively and compose their deathless papers. Every step of the investigation duly documented, another heavy brick would eventually be placed in the walls of the great edifice of science. Real, permanent, lasting.

This quantity and solidity matter in science. In its culture, less usually isn’t more. In the geological exaltation of every valley and mountain, every reference and exposure shall be made plain. Every scrap of fact shall be recorded. And the more effort, the more stitching that shows, the better - because the stitching (the sacred data) is the point.

Small wonder then, that those who work to achieve something as momentary and transient as a newspaper article or radio interview often find their work leaves the scientists who get caught up in it puzzled, infuriated – and frequently alienated. Mayflies do not mate easily with termites. What we do helps define our psychology. Why else would scientists be so obsessively literal-minded? Why would we so often find among them the odd conviction that any form of communication can be evaluated according to its efficiency in coveyancing factual information? Not for them, Turrell’s "wordless thought that comes from looking in a fire".

It is difficult not to love the idea of science as a common, democratic project that finds a useful place for average as well as the brilliant. It makes the arts seem – like Nature herself - horrifically cruel and wasteful. Unfortunately, as Harry Lime reminded us, democracy exacts a price. The Swiss paid for it in cuckoo clocks. Scientists pay for it every time they decline to leave their nest and fly with the mayflies.

[The light fantastic by Mick Brown: Telegraph Magazine January 2002 pp34-41. See also Turrell’s Tunnelling by Tom Kemp in Visualizations – the Nature book of art and science pp136-7 Oxford University Press, 2000.]