The interdisciplinary international meeting Earth System Processes (Edinburgh, June 2001) was a symbol of how geoscientists should involve the public. From Geoscientist October 2001

In 1960 the English scientist, statesman and novelist C.P. Snow opened his address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science with the bold statement "Scientists are the most important occupational group in the world today". Our age has become shy of such sweeping value judgments, though no one would deny that scientists’ work empowers the human race like no other philosophy in history.

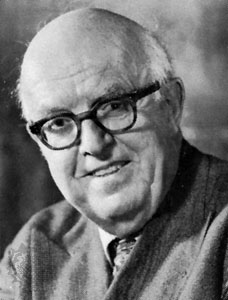

Charles Percy Snow (1905-80, or Lord Snow as he became in 1964) was a man with a keen sense of public duty, especially as applied to scientists. His novels explore these ideas in detail, but is perhaps best remembered as the originator (in his 1959 Rede Lecture) of the concept of "the two cultures" – the dichotomy of science and literature.

It was an important observation, though the phrase has become so familiar that its original meaning is sometimes lost. When people use it today they often tend to mean "the culture of scientists versus that of everyone else". It has become shorthand for the isolation of science in society – though that is a separate evil, and one that in 1960 was still quite a long way off. In that era of modernism and progress, scientists did have all the answers and people believed them. Soon we would be riding moving walkways in the sky like the Jetsons, and living on coloured pills. The white coat had not yet gathered its stains.

Scientists were isolated then too; but they were happy monarchs, because they were loved. Only when the peasants became revolting did their isolation become a "problem" that needed to be addressed – and not before time. Thus was born the Public Understanding of Science (PUS) – a top-down movement motivated mainly by scientists’ desire to recapture their former adulation. The original PUS movement was rooted in the "we know best" attitude that had already had its day. It was special pleading of the worst sort – part of the problem, not the solution.

The undoubted power of their work to influence people’s lives places scientists in a unique public position, as Snow realised. However, Snow’s perception of the problem stemmed partly from his (physicist’s!) belief in the certainty of scientific knowledge, and his proposed solution turned out to be inappropriate when the time came. This was because being top-down, it ran counter to the spirit of an age that questioned science’s pretension to be the arbiter of all things.

The joint GSA/GSL meeting Earth System Processes (Edinburgh, Scotland, 24-28 June 2001) explored the inter-relatedness of all Earth sciences. In so doing, however, it also showed how the same participative approach also provides the practical answer to forging a new relationship between scientists and the public.

The key to a healthier relationship with the public lies not primarily in the public understanding of science (important though that is), but in scientists’ understanding of the public. For this to happen, there is an overriding need for scientists to show cultural respect – respect for other professional micro-cultures involved in the process (journalists, public relations officers, politicians, policymakers, civil servants) as well as for true cultures very different from the one in which most scientists grow up. Until scientists treat others with the respect they expect for themselves, they won’t get anywhere.

In the simplest practical terms for organizations this means not expecting the world to beat a path to your door. David Applegate of the American Geological Institute opened a session on public communication of environmental issues and hazards with a review of how the United States Geological Survey (USGS) was nearly eliminated in 1995 – not because its work was thought shoddy, but because nobody in the administration appeared to know what it did. Much the same thing once happened in the UK, when an aspiring young chief secretary to the Treasury, Mr John Major, is reputed to have pointed to a cost head on a balance sheet and asked "What is the Geological Survey – do we need one? Can we cut it?"

Where ignorance exists it is the fault of the educated. But to tackle it requires permanent interaction with both policy-makers and public. As Applegate said, "efforts to affect public policy cannot be separated from efforts to improve public awareness". You can and must talk personally to politicians - but if it’s their hearts and minds you are after, you must first have them by those parts of the anatomy recommended by President Lyndon Baines Johnson. In other (politer) words, the voting public.

Communication of risk is all about the communication of uncertainty. It is interesting to read, in Snow’s AAAS address, his naïve faith in scientific certainty. How different things seem today. The idea that somehow scientific knowledge possesses a higher order of certainty is a piece of self-flattery that today the public has identified as deceptive. The public understands that scientific knowledge is provisional, and its prognostications tentative, at least in all that which is interesting, complex, cutting edge, or which might influence the way you live, the food you eat, or whether you worry about global warming. The facts may be OK – it’s the conclusions you draw and the action you take that are important, and they are nothing like as certain.

Understanding uncertainty is inherent in knowing the difference between prediction and forecasting. Nobody expects the weather service to say it will rain outside your front door at 13.42. Why should volcanologists or seismologists be able to do any better? While much of the public still expects prediction, most scientists are only offering improved forecasting. Scientists have to manage that expectation. (That’s "scientists understanding the public".)

Next comes the need for education – the "public understanding of science". Craig Weaver (USGS, University of Washington, Seattle WA.) described how the USGS Earthquake Program (Seattle) has taken a multi-pronged information and educational approach. By exposing the limits of science’s potential, the Program educates the public so as not to expect the impossible. Only after this is done can scientific information be taken in the correct context. Both approaches are needed, in the right order. If the public mistakenly expects prediction, then it will interpret scientific information wrongly. Scientists must explain the limits of their knowledge; the necessary humility is crucial to good communication.

Weaver also emphasized the failings of the "love them and leave them" approach. Public relations is never finished. The public must be continually involved– not only as recipients, but as contributors – as in the Cascadia Regional Earthquake Workgroup. "Working, together with the public" best describes the best practice. As Weaver said, "Too often the USGS has a limited perspective of real-world issues, and we must listen critically to better match our capabilities with needs".

Native American tribes in Washington State have lived in harmony with their environment for millennia. For these tribes of the Pacific Northwest Indian, integrating their own close and spiritual relationship with the land with modern science is now a practical reality, keeping precious resources vibrant for future generations. But now, water pollution and development are threatening the precious resources on which their way of life depends, as 29 tribes in Washington State find their natural resources under threat.

The Suquamish and the Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribes asked geologists to help them manage water quality through a long-term approach. David Fuller is a water resources manager and hydrogeologist for the Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe, and he provided an overview of the approaches, projects and activities these two tribes have taken to address their water concerns during a session on Integrated approaches to water quality issues.

One superb example he described is the Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe's review and analysis of a leaking unlined landfill site. Although it lies off-reservation, it also lies up-gradient, and nature does not respect human boundaries. The toxic plume from the unconfined aquifer reaches the surface on the Port Gamble S'Klallam Indian Reservation - as the headwaters of small creeks. These then flow less than half a mile into the shellfish beds of Port Gamble Bay. The Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe is now working with the State of Washington (the landowner) and the landfill operator to remediate the problem.

"Tribal activities and technical participation have made definite impact to regional water resource programs," Fuller said. "The Suquamish and Port Gamble S'Klallam tribes have provided leadership roles on local, county, and State water resources studies, water resource planning committees, and technical advisory committees."

"We provide the professional community with the recognition that tribes are out there using science, and have both data and understanding to contribute to the environmental and scientific community" Fuller explained. "My perspective on the tribal approach, and direction I have received, is to look at the big picture and long time frame. Most of my clientele hasn't been born yet and won't be for some time to come!"

Earth System Processes showed how scientists from different disciplinary backgrounds benefit from seeing their individual subjects as part of a greater whole - the study of the Earth system. Likewise, scientists as a group need to see themselves as part of a continuum with other cultural forces, and engage them in a constructive, participatory way. Only then science will regain the public respect it feels it has lost.

Lord Snow was right about the problem, but wrong about the method. It’s not just about two cultures. It’s about all cultures. I am happy to build a bridge with literature in closing with E.M. Forster, who said it all in two words: Only connect.