Ted Nield describes Britain’s worst mining-related disaster 50 years ago this month, from which grew a new awareness of engineering geology’s importance.

"But it will roll down on top of us” I said. “In time to come, I suppose,” he said, but not taking much notice. “Years, yet.”’

Richard Llewellyn, How Green Was my Valley (1939).

On 21 October 1966 the worst mining-related disaster in British history took place in Aberfan, a small village in the valley of the River Taff, between Merthyr Tydfil and Cardiff. It took place in a community whose single mine, the Merthyr Vale (or ‘Nixon Navigation’ as it was known before nationalisation in 1947) had never seen a major disaster. It was also remarkable because of the 144 people killed, 116 were children.

On 21 October 1966 the worst mining-related disaster in British history took place in Aberfan, a small village in the valley of the River Taff, between Merthyr Tydfil and Cardiff. It took place in a community whose single mine, the Merthyr Vale (or ‘Nixon Navigation’ as it was known before nationalisation in 1947) had never seen a major disaster. It was also remarkable because of the 144 people killed, 116 were children.

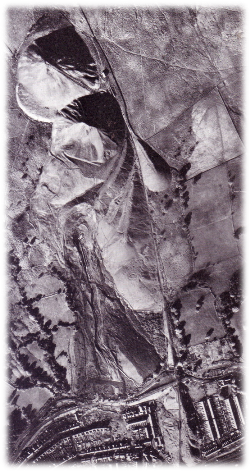

Picture: Aerial photo in low light showing the bulge in Tip 5 (top) and the failed Tip 7. Traces of the 1944 slide from Tip 4 can also be made out in the hummocky ground just above and left of the 1966 slide. From the Tribunal report.

In 1966, Mynydd Merthyr, the ‘Pennant Sandstone’ mountain on the west side of the Taff Valley, supported seven huge spoil heaps containing an estimated 2.6 million cubic yards of mine waste. Highest on the horizon stood two conical tips, (Nos. 4 & 5), begun in 1933 and 1945. The other tips, lower on the hillside and numbered 1,2,3, 6 and 7, built out in southward-pointing arcs like rococo festoons, from a mineral line which brought the journeys of waste-filled drams from the colliery to their heads.

Crane tipper

These linear tips were created by a crane tipper (right), which ran on its own short length of horizontal track along the tip’s contour-hugging crest. The crane would pick each dram up, invert it to spread its contents downslope, and then return it upright to a steel plate, which then guided it back onto rails again. Only one of these tips – Tip 7 - was active at the time of the disaster, and it was this tip that collapsed and avalanched into the village, wiping out everything in its path and destroying Pant Glas Junior School, where the children died in their classrooms on the last day before half term.

These linear tips were created by a crane tipper (right), which ran on its own short length of horizontal track along the tip’s contour-hugging crest. The crane would pick each dram up, invert it to spread its contents downslope, and then return it upright to a steel plate, which then guided it back onto rails again. Only one of these tips – Tip 7 - was active at the time of the disaster, and it was this tip that collapsed and avalanched into the village, wiping out everything in its path and destroying Pant Glas Junior School, where the children died in their classrooms on the last day before half term.

Picture: Tipping crane and drams on site, presumably Tip 7. Photo from www.alangeorge.co.uk.

Tip No. 7 was started in 1958. By 1966, it contained 297,000 cubic yards of waste, 30,000 of which were of a fine slurry called ‘tailings’ - waste products of the coal preparation plant. The other tips contained no such fine tailings. Tip 7 did not need these tailings to make it fail; but their presence did affect the quality of the material that overwhelmed the village.

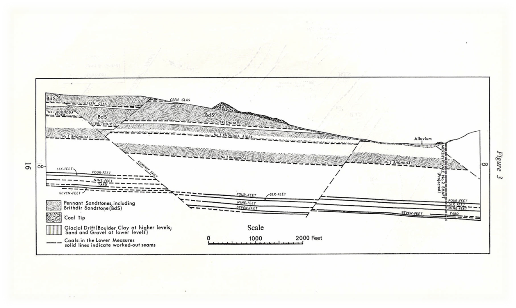

The culprit, of course, was not the tip material itself, but water. The sandstones of Mynydd Merthyr on which these huge accumulations rested are Westphalian in age and are riddled with impervious partings and minor coals. Spring lines are common, as rainwater (almost two metres of which falls every year) percolates down through the sandstone and forces its way up to the surface along the partings.

The culprit, of course, was not the tip material itself, but water. The sandstones of Mynydd Merthyr on which these huge accumulations rested are Westphalian in age and are riddled with impervious partings and minor coals. Spring lines are common, as rainwater (almost two metres of which falls every year) percolates down through the sandstone and forces its way up to the surface along the partings.

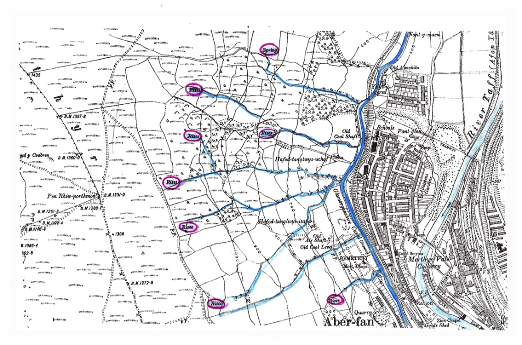

Picture: OS ‘six inch’ map 1919, showing Aberfan before the commencement of tipping West of the Taff, on Mynydd Merthyr. The need for new tipping space was made urgent by mechanisation, which vastly increased the amount of spoil brought to surface. From the Tribunal report.

The Geological Survey sheet clearly illustrates where these crop out, while Ordnance Survey base-maps (left), made and remade from 1874 through 1900 and 1919, are dotted with the words ‘Rises’ and ‘Spr.’ Despite all that was said in the aftermath of the Disaster, everyone knew about them. A tip on a steep mountainside riddled with springs in a high rainfall area above a village is a disaster waiting to happen. In fact, the tips themselves were already speaking eloquently of their unsuitable siting and the inadequacy of their civil engineering design – which was, in fact, notable only by its complete absence.

Maclean tippler

Maclean tippler

Tip 4, for example, begun in 1922 and the second highest after Tip 5, was a conical ‘Maclean Tippler’ tip. No surveys of its eventual footprint were carried out, and from the positioning of its central steel tower it was obvious that, as it grew, it would spread to cover the source of a major stream. No drainage was attempted, and no effort made to culvert the streams that would eventually be engulfed. Instead, the sources were duly covered and continued to bleed into the base of the growing heap. On 27 October 1944, the inevitable happened; a large portion of Tip 4 failed and slid down the mountainside for almost 600 metres, stopping just a hundred metres or so short of the disused Glamorgan Canal.

Picture: Post-disaster (1966) contour map of tipping at Aberfan. 1966 slide (dotted outline), principal springs (B1, B2) and streams. Tips numbered 1-7. From the Tribunal report.

If one definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result, tipping practices above Aberfan were truly insane. As the Tribunal, convened after the 1966 Disaster to inquire into its causes, put it: the 1944 slide ‘provided a constant and vivid reminder (if any were needed) that tips built on slopes can and do slip, and having once started… travel long distances’.

NCB regulations

Very few people ever heard about the slip of 1944, and none at National Coal Board (NCB) headquarters. According to NCB regulations, there had simply been no need to report it, since no person working at the mine had been hurt. As the author of the Tribunal report, Sir Herbert Edmund Davies, acidly observed: based on that criterion, the colliery would not even have had to report the 1966 Disaster either! Nevertheless, failure of No. 4 tip rendered it useless, and Tip 5 - which was to grow to be the tallest - was begun, in 1945, on the same plan, higher up the mountain, after no ground investigation or preparation of any kind.

Unsurprisingly therefore, it too eventually covered a spring and its watercourse to a distance of about 300 metres. By 1951, aerial photographs clearly showed a large and ominous bulge growing on its south east flank; yet no precautions against its possible failure were taken during the five remaining years its life, which ended in 1956. It has never been clear why Tip 5 was abandoned, though the three factors probably were - incipient slippage, enormous size (706,000 cubic yards) and the fact that it was by then also partially alight.

Unsurprisingly therefore, it too eventually covered a spring and its watercourse to a distance of about 300 metres. By 1951, aerial photographs clearly showed a large and ominous bulge growing on its south east flank; yet no precautions against its possible failure were taken during the five remaining years its life, which ended in 1956. It has never been clear why Tip 5 was abandoned, though the three factors probably were - incipient slippage, enormous size (706,000 cubic yards) and the fact that it was by then also partially alight.

Picture: Section through the geology of Aberfan, E-W, with true vertical scale. BdS – Brithdir Sandstone (Westphalian), otherwise known on the South Crop as the ‘Pennant Sandstone’. From the Tribunal report.

In 1956, dumping switched to Tip No. 6, a linear tip lower down the mountain, the only one sited north of the mineral line, and the only one to build out at right angles to slope, rather than along contour. No plans were produced, and no precautions against slippage were taken. Tip 6 had a short, uneventful life, brought to an end not by failure but by a letter from a neighbouring farmer, pointing out that the Coal Board was tipping on land that didn’t belong to it. A survey was hurriedly ordered to determine what land exactly the Board did own on Mynydd Merthyr. As Group Planning Engineer Mr Warwick James Strong soon found out, farmers are rarely mistaken in such matters. The colliery needed a seventh tip. The fate of 116 unborn children was about to be sealed.

No thought

For the site of Tip 7, NCB managers turned to land south of the mineral line - immediately downslope from Tip 4, which slipped in 1944. This meant that Tip 7’s growth trajectory would eventually take it directly across the slipped material from Tip 4, and the very same watercourse that had caused that failure. But, as the Tribunal report noted: ‘No one gave any thought to the ultimate maximum area of Tip 7’.

For the site of Tip 7, NCB managers turned to land south of the mineral line - immediately downslope from Tip 4, which slipped in 1944. This meant that Tip 7’s growth trajectory would eventually take it directly across the slipped material from Tip 4, and the very same watercourse that had caused that failure. But, as the Tribunal report noted: ‘No one gave any thought to the ultimate maximum area of Tip 7’.

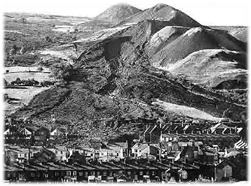

Picture: View taken from the Old Black Bridge (Aberfan Bridge), which carried the roadway across Aberfan Road and up Mynydd Merthyr. Photo by Tony Richards from www.alangeorge.co.uk.

The men responsible for siting Tip 7 were Ronald Neal Lewis, Group Manager, and Joseph Baker, Group Mechanical Engineer. Neither had any background or education in tip design, civil engineering or geology. No survey was taken, no consideration of geological or geographical features given, and no guidance as to its ultimate extent was ever issued to Mr Robert Vivian Thomas, the colliery engineer whose job it became to supervise it. One of the most telling pieces of evidence laid before the Tribunal, in its unprecedented 76 days of hearings in Merthyr Tydfil and Cardiff, was that when Messrs. Lewis and Baker set off up Mynydd Merthyr on that fateful day to decide the siting of Tip 7, they took no map with them of any kind.

Disaster

Picture: Conical tips 5 (top) and 4; The short-lived Tip 6, far right. Photo by Tony Richards from www.alangeorge.co.uk.

Picture: Conical tips 5 (top) and 4; The short-lived Tip 6, far right. Photo by Tony Richards from www.alangeorge.co.uk.

The 21st of October 1966, almost 20 years to the day since the 1944 slide, dawned calm and windless. Mist hung low in the valley, hiding the mountain tops from view as the children made their way to school – juniors for the bell at nine o’clock, seniors for half past. The slopes of Mynydd Merthyr stood high above the mist. The first of the men working Tip No. 7 arrived just before half past seven, though without their Charge Hand, Leslie Davies. He was at the colliery, giving his weekly Friday report to Colliery Engineer Vivian Thomas. Mr Gwyn Brown, who operated the crane, and slinger David Jones walked to the point of Tip 7, and saw the pit-heads and the boilerhouse chimney of Merthyr Vale Colliery poking up through the blanket of white mist.

However, when they inspected the active point of the tip, as they did each day before moving the crane up ready for work, a more disturbing sight greeted them. The rails on which it travelled had now fallen into a pit, three metres deep. Not liking the look of this, Brown suggested to Jones that he contact their Charge Hand at the colliery. Unfortunately, colliery managers had removed the gangers’ telephone, following a series of cable thefts; so Jones set off, leaving Brown and others to retrieve the landing-plate, and move the crane back from the edge.

Depression

Back at the mine, Jones found his Charge Hand, who reported the news to the Colliery Engineer. An oxy-acetylene cutter team was despatched to cut off the overhanging rails; Thomas ordered Davies to stop tipping and told him that, on the Monday following, he would come on site himself and find a new tipping-place. Davies, Jones and two men with cutting equipment climbed back up Merthyr mountain, arriving at nine o’clock. While they had been away, the depression had doubled in depth.

Davies told Brown to move the crane further back; but before doing anything they all retired to their cabin for a well-deserved cup of tea. Brown alone remained. As he stared down from the edge of the depression, he suddenly saw it begin to rise back up.

Davies told Brown to move the crane further back; but before doing anything they all retired to their cabin for a well-deserved cup of tea. Brown alone remained. As he stared down from the edge of the depression, he suddenly saw it begin to rise back up.

Picture: Aberfan disaster landslip, from the opposite side of the Taff valley, showing the rotational slip at the head of the landslip, and the toe reaching into Moy Road, and Pantglas School. Photo from www.alangeorge.co.uk.

“It started slowly at first” he told the Tribunal: “I thought I was seeing things. Then it rose up after pretty fast, at a tremendous speed. Then it sort of came up out of the depression and turned itself into a wave – that is the only way I can describe it – down towards the mountain… toward Aberfan village... into the mist.”

His shouts brought Leslie Davies and the others out of the cabin, and they all ran for their lives, a deafening roar following them. Blindly in the mist they shouted to each other, as they descended tips 3, 2 and 1; “All I could see was waves of muck, slush and water… I couldn’t see – nobody could.”

The mountainside farmhouse and cottages at Hafod Tanglwys Uchaf lay directly in the path of the slide and were wiped off the map, killing everyone within. One hundred and forty thousand cubic yards of black slurry then hit the disused canal, fracturing the water main that had been laid along it, and leaping the old railway embankment. Once in the village, the slip destroyed 18 houses, Pant Glas Junior and part of the neighbouring County Secondary School, before finally coming to rest on the Aberfan Road. It was now 0915.

The last child brought alive from the filthy morass emerged at 1100. Bodies continued to be found days later. In total, 144 lives were lost, 116 of them children aged mostly between seven and ten. One hundred and nine perished in the junior school. Of the 28 adults who died, five were primary school teachers.

Mr George Williams, a barber in Moy Road - one of the worst affected streets - had been on his way to open up. He was expecting a busy day - people wanting to look their best for the weekend. He heard a roar through the fog, but saw nothing until the windows, doors and then the walls of Moy Road houses burst and collapsed ‘like dominoes’ before his eyes. Protected by a sheet of corrugated iron, he was dug out later by council workers. What he remembered, he said, was the hush – “like turning off the wireless…you couldn’t hear a bird or a child”. At 0920, the hooter at the colliery that had never suffered a major disaster, broke its long silence.

Responsibility

Responsibility

Picture: Aberfan in 1968, from the SE. Foreground – the Merthyr Vale Colliery and marshalling yards. The remains of collapsed tip 7 are in the process of being cleared. Other tips still remain. Photo by Tony Richards from www.alangeorge.co.uk.

Today, responsibility between forebears and descendants is called ‘intergenerational equity’ – an incomprehensible term for a simple idea: that present generations should not by their actions jeopardise future ones, expressing the natural instinct of every parent. What happened in Aberfan was a mass betrayal of intergenerational equity. Parents, who knew that they owed their children a better chance in life, looked at what had happened, and however undeservedly, felt themselves weighed in the balance and found wanting. Worse, they felt complicit. Nothing makes the knife-blade of grief sharper than the alloy of guilt, and as television spread its images across the world everyone shared the feeling - even those whose complicity amounted to no more than shaking a scuttle of coal onto a household fire. Who, indeed, could look on as another little, limp body was pulled free from the slurry, without feeling that they could and should have done more, however insignificant? Many dropped everything and went. From all over the world, money and toys poured in.

In the village, many instinctively tried to ease the pain with which they, however unjustly, burdened themselves, by finding scapegoats, notably the unfortunate gangers on the tip; men whose conduct was completely and explicitly exonerated at the Tribunal. There was no shortage of genuine culprits named in the Tribunal’s report – though, as it also admitted, there were: ‘no villains in this harrowing story … of bungling ineptitude, by many men, charged with tasks for which they were totally unfitted; … decent men, led astray by foolishness or by ignorance, or by both in combination.’

Robens

Sadly, no matter how vivid and well-deserved the condemnation, the people of Aberfan found their pain was not eased. Nothing, truly, could have done that; though it did not help that no prosecutions followed, nor that the Coal Board Chairman, Lord Robens, and many others, clung successfully to their jobs after initially denying responsibility. The Aberfan Disaster Fund finally reached £1.7m; though few who donated would have expected that £150,000 of the money they intended to help the bereaved would be used to pay for clearing away the remaining tips, after both the NCB and the Treasury refused to do so.

Nor did it help that, despite being a clear breach of charity law, Robens’s raid on the Fund went unchallenged – and remained without redress until 1997, when the Blair Government finally paid the money back (without interest). The Tribunal report may have been a masterpiece of judicial writing; but it too was betrayed by events that followed – or rather, failed to follow - its publication in July 1967. Today, as a result, many people wrongly assume it was a whitewash.

The Aberfan Disaster not only ripped the heart out of one small Welsh village – it sucked life out of an entire industry. The eerie silence that followed the landslide also fell upon the phrase ‘the heroism of mining’. This rhetorical chestnut had stubbornly survived its own debasement, in generations of political speeches, and still resonated with ordinary people. It passed completely out of use. Even ‘the dignity of labour’ seemed to lose meaning as a generation, in the extremity of its grief, cursed all their forefathers, threw down their monuments, and turned their faces to the Earth in shame.

* Ted Nield’s Great Grandfather William Bowen (1856-1922) was Overman and Undermanager at the Nixon Navigation (Merthyr Vale) mine. Ted (b. 1956) is the same age as most of the children who died in 1966. His parents, both schoolteachers, are now buried in Bryntaff Cemetery, Aberfan. Fortunately, they had made their life in Swansea. See Underlands, (Granta Books) from which this article is a modified extract.

* Ted Nield’s Great Grandfather William Bowen (1856-1922) was Overman and Undermanager at the Nixon Navigation (Merthyr Vale) mine. Ted (b. 1956) is the same age as most of the children who died in 1966. His parents, both schoolteachers, are now buried in Bryntaff Cemetery, Aberfan. Fortunately, they had made their life in Swansea. See Underlands, (Granta Books) from which this article is a modified extract.

Further reading

- George, Alan: Old Merthyr Tydfil website www.alangeorge.co.uk. See ‘Aberfan’ and especially the subsection on ‘The Aberfan Disaster’. Several pictures used in this article were taken from this excellent online photographic record.

Acknowledgements

The author extends his thanks to historian the late Alan George, who died on 27 October 2015, aged 70. Alan’s website ‘Old Merthyr Tydfil’ (W: www.alangeorge.co.uk/old_merthyr.htm), its associated Facebook page, and contributions from many local photographers like Tony Richards, has grown into a rich resource of photographic and anecdotal evidence for all those interested in industrial history.

Save