After the closure of Kellingley, what does the Coal Authority do? Richard Hughes and Steven Kershaw* talk to Geoscientist.

Coalfields underlie some 26,000 km2 - 11% - of the surface area of England, Scotland and Wales. Since the start of the industrial revolution, human settlement has followed natural resources, industry and employment - and coalfields today are consequently some of the UK’s most densely populated regions.

Coalfields underlie some 26,000 km2 - 11% - of the surface area of England, Scotland and Wales. Since the start of the industrial revolution, human settlement has followed natural resources, industry and employment - and coalfields today are consequently some of the UK’s most densely populated regions.

Some seven million properties lie within them; 1.5 million lie above workings where coal has been mined at depths of less than 30m, and at least 172,000 coal-mine entries are known. Although there is relatively little active coal-mining today, and all deep coal-mining has now ceased, centuries of underground and surface extraction have left a huge legacy of environmental issues and public safety hazards.

Picture: Adequate regulation is essential to ensure full post-extraction site restoration.

The Coal Authority was created under the 1994 Coal Industry Act, when the previously state-owned coal industry was privatised, to regulate the industry and manage its various legacy issues.

Later, the 2011 Energy Act expanded the Authority’s remit to include the treatment of non-coal mining legacy issues. Today, its main functions are:

- protecting the public and property from the effects of surface mining hazards and subsidence,

- managing and treating contaminated coal and non-coal mine-waters,

- providing mining hazard information for conveyancing, property development and risk management,

- providing planning guidance as a statutory consultee, and

- licensing and regulating coal extraction.

Mining information

Data underpins every aspect of the Authority’s work. Its digital coal mining data-sets derive largely from c. 120,000 mine abandonment plans, held on behalf of the Health and Safety Executive in the Authority’s purpose-built records centre in Mansfield, north Nottinghamshire. Over the past 30 years these plans have been digitally captured, interpreted by mining surveyors, and integrated with other data to produce unique, digital data-sets documenting the history of coal-mining activity. Data are updated daily with new information from coal operators, site investigations and other sources.

Data underpins every aspect of the Authority’s work. Its digital coal mining data-sets derive largely from c. 120,000 mine abandonment plans, held on behalf of the Health and Safety Executive in the Authority’s purpose-built records centre in Mansfield, north Nottinghamshire. Over the past 30 years these plans have been digitally captured, interpreted by mining surveyors, and integrated with other data to produce unique, digital data-sets documenting the history of coal-mining activity. Data are updated daily with new information from coal operators, site investigations and other sources.

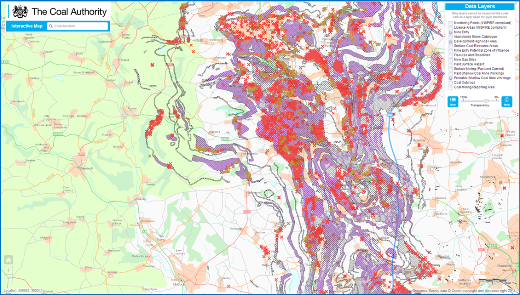

Picture: Coal Authority digital mining data for north Derbyshire. (Topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping © Crown Copyright and Database Right 2011).

Much of the Authority’s spatial mining hazard data can be viewed free of charge on the web, and high resolution data sets are now available for commercial licensing. The Law Society of England and Wales advises conveyancers to purchase a mining search report for all property transactions in coalfields. The main delivery channel for the Authority’s coal mining information is therefore a property-specific mining search report. Its unique, fully automated reporting system produced c. 340,000 of these in 2014/15, with 99% of all reports ordered and dispatched digitally, with a turnaround time measured in minutes.

Data are vital to the Authority’s work as statutory consultee for planning applications, enabling risks to development from mining to be identified. For planning purposes ‘low’ and 'high risk’ areas are identified on county maps, available for download free of charge. In ‘high risk’ areas the Authority’s planning team processes consultations on some 5500 planning applications and 500 development plans each year - deciding whether further research or a site investigation is required before development can proceed. If a site investigation is deemed necessary, the Authority will issue an access permit to the workings and evaluate the techniques to be used, ensuring that any risks to public safety are adequately managed.

Public safety

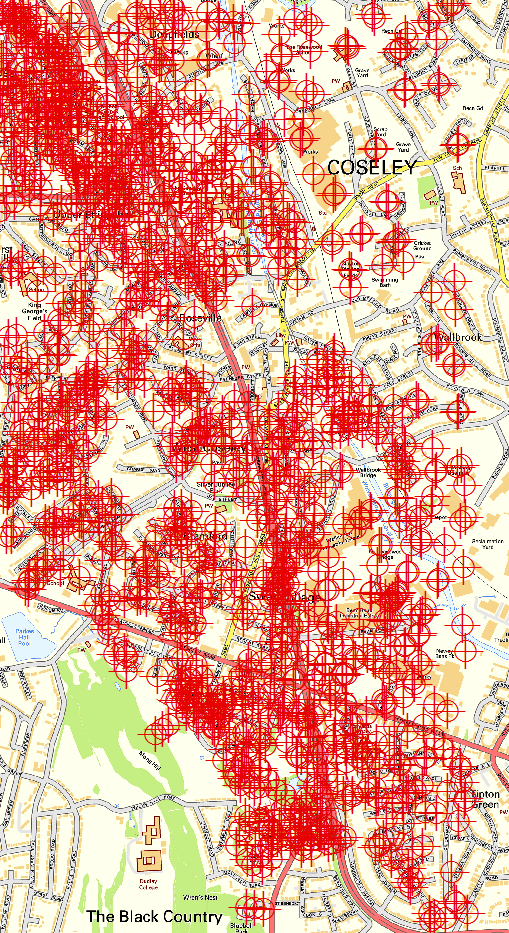

Picture: Density of mine entries in an urban setting, West Midlands. (Topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping © Crown Copyright and Database Right 2011).

Picture: Density of mine entries in an urban setting, West Midlands. (Topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping © Crown Copyright and Database Right 2011).

One third of the 172,000 documented coal mine entries are to be found in what are now urban areas, so a substantial legacy of mining hazards remains within many major conurbations. Surface collapses above abandoned workings and shafts present the most common risks to the public. A ‘hazard line’, open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, enables the public to report mining hazards around the clock – and the despatch of immediate responses. About 1000 surface incidents are reported each year, roughly half of which turn out to be mining-related.

The scale of these issues means that costly proactive remediation of the surface effects of shallow mineworkings and mine entries is carried out only where there is a high risk to persons or property. Known shafts represent discrete high-risk zones, and in 2008 the Authority began a mine-entry inspection programme to identify such locations for proactive remediation. To date, some 130,000 shafts have been inspected – of which 1 % required remedial attention.

Most typically, damage caused by shallow workings occurs when the collapse of the mine roof migrates to the surface, forming a ‘crown-hole’. Collapses of deep, unfilled shafts may be more serious, especially where thick superficial deposits can create a cone of failure tens of metres across. In a recent example in Scotland, one of a pair of adjacent shafts collapsed, threatening to draw an adjacent residential property into the void. Treatment required demolition of two residential properties, allowing the shafts to be grouted and sealed with a reinforced concrete cap.

‘Non-standard’ shaft collapses require more specialist treatment. A recent example in north east England occurred in a shaft that also acts as a discharge point for mine waters. To prevent the shaft from collapsing in on itself and affecting nearby buildings, a silicate resin foam plug was installed. Final treatment involved the sinking of a 10.5m diameter pre-cast concrete segmental caisson to a depth of 7.5m around the collapsed shaft, enabling the failed section to be demolished, removed and re-built with pre-cast concrete sections. The shaft cap was constructed with an aperture, to allow mine waters to rise and fall within the new shaft section.

Tips and escapes

There are estimated to be over 5000 colliery waste tips in England, Scotland and Wales, with over 1200 in the South Wales coalfield alone. Most of these tips belong to local authorities and major landowners, but the Authority manages 41 of the largest sites - including Aberfan. This was the site of a major disaster 50 years ago this year, when failure of a tip caused 144 deaths. (Geoscientist will publish a special commemorative issue about Aberfan in October). Today, the Authority’s expertise is also being applied to the management of abandoned metalliferous mine tips and settling ponds in other parts of England.

Gas escapes from abandoned mines to the surface present a significant risk to the public, and have caused fatalities over the years. The principal risks come from explosion due to the escape of methane, and asphyxiation by low oxygen/high carbon dioxide mixtures, known commonly as ‘blackdamp’. These risks are greatly increased where gases leak into buildings and other confined spaces.

Vents are installed in workings suspected of containing gas at pressure, which are regularly monitored for any changes in gas composition. Two protective pumping schemes have been installed in north east England to prevent the ingress of gas into residential properties, while elsewhere, mine gas is allowed to vent naturally into the atmosphere.

Mine water

Significant environmental impacts can arise from contaminated mine waters, which are typically rich in soluble iron derived from minerals such as iron pyrites. When these reach the surface, oxidation causes precipitation of iron ochre, which is toxic to flora and fauna and discolours natural watercourses.

Significant environmental impacts can arise from contaminated mine waters, which are typically rich in soluble iron derived from minerals such as iron pyrites. When these reach the surface, oxidation causes precipitation of iron ochre, which is toxic to flora and fauna and discolours natural watercourses.

Under the European Water Framework Directive (WFD) member states are required to maintain their water bodies at ‘good’ status. The Authority works with the Environment Agency, the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency and Natural Resources Wales to identify and treat sites so that they comply with the WFD. To this end, the Authority has designed and operates over 70 mine-water treatment schemes in England, Scotland and Wales.

Pictures left, right: Saltburn Gill before and after mine-water treatment.

Mine water is either pumped or allowed to reach the surface naturally. Pumped schemes are used to prevent uncontrolled emissions, or to prevent contamination of aquifers. At surface, the water is then treated either passively (using settling lagoons and reed beds), or using an active plant.

Passive treatment is used for most coal-mine waters. A typical scheme will use an aeration cascade to accelerate the release of carbon dioxide from solution and increase oxygenation, both of which catalyse iron precipitation. Most settles out in the lagoons, from which the water is then passed through reed beds to reduce its iron content further – typically to less than one milligram per litre - before entering streams, rivers and the sea.

Passive treatment is used for most coal-mine waters. A typical scheme will use an aeration cascade to accelerate the release of carbon dioxide from solution and increase oxygenation, both of which catalyse iron precipitation. Most settles out in the lagoons, from which the water is then passed through reed beds to reduce its iron content further – typically to less than one milligram per litre - before entering streams, rivers and the sea.

To prevent contamination, the Dawdon treatment scheme in County Durham treats saline, iron-rich water pumped from mine workings below an aquifer serving the conurbations of the north east. The Authority is currently working to exploit the considerable geothermal potential of this, and other, pumped treatment systems.

Waters from abandoned metal mines typically do not contain high levels of iron and therefore often appear clean and even drinkable, despite being rich in toxic metals. In contrast to coal, no single organisation has responsibility for dealing with the legacy of metalliferous mining. However, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) funds the Coal Authority to treat metal-mine waters in England, and three such schemes are operational.

Iron-rich waters from an abandoned ironstone mine in Cleveland once issued into Saltburn Gill (left, right, above), which then ran over a beach and into the North Sea. The scheme has now removed this eyesore, improving water quality and the amenity value of the beach. A second scheme treats water from the abandoned former lead-zinc and baryte Force Crag mine in the English Lake District, preventing contamination of Bassenthwaite Lake. This scheme uses a vertical flow-pond system and employs sulphate reducing bacteria to precipitate metal sulphides within the compost substrate - removing over 98% of zinc, 94% of lead and 94% of cadmium in its first year of operation.

The Authority also manages the abandoned Wheal Jane metal mine in Cornwall on behalf of Defra. Between April 2014 and March 2015, 5.4 million cubic metres of water were abstracted to maintain the water at safe levels and prevent polluted waters from issuing into the Fal estuary. An active plant treats the water, removing during the same period over 90% of contaminants (including one tonne of copper, 0.1 tonne of cadmium, 127 tonnes of zinc, 15 tonnes of manganese and 7 tonnes of arsenic!).

Mining regulation

Picture: Mine gas vents at the Stadium of Light, Sunderland.

Picture: Mine gas vents at the Stadium of Light, Sunderland.

Strong regulatory practice – before, during and on closure of extractive operations – is essential for managing long-term mining impacts, and encourages investment by providing stability and certainty for mine developers. The Authority regulates and licenses coal mining operations, and works with other regulatory bodies on mining matters. The Authority’s Independent Compliance Unit (ICU) provides restoration liability bond assessment services to other public bodies (such as local authorities), ensuring that liabilities are understood and quantified before and during mining operations.

Research & innovation

The Authority sponsors research to understand and help reduce any risks from mining legacy hazards. Trials and research are carried out into the basic mechanisms associated with removal and precipitation of iron from coal-mine waters. These include the effects of aeration and oxidation on the residence time to allow for optimum precipitation, and the contribution of bacteria and plants to schemes’ performance. The Authority also works with Defra, the Environment Agency and university partners to trial new physical and chemical techniques for metal-mine water treatment.

The Authority’s engineers have also investigated the use of alternative materials for sealing mine entries and carried out field trials on the behaviour of rock and resin composites. Using such methods could have significant environmental and cost benefits over standard ‘concrete and steel’ solutions, especially in remote or difficult-of-access areas.

Future

Picture: Collapsed shaft treatment in north east England.

Picture: Collapsed shaft treatment in north east England.

The Coal Authority is proud of its 20-year record of safeguarding the public, property and the environment from the adverse impacts of mining. Historically this has been paid for by government, but maintaining and growing this valuable work at a time of considerable pressures upon public finances presents many challenges.

In response, the Authority has embarked on a strategy to make itself less dependent upon public funding. The pillars of this strategy are to fully realise the economic value of our people and our unique information assets. The Authority is also working to exploit the commercial value of waste products such as iron ochre, and geothermal energy from its mine-waters.

All our regulatory and legacy management services are now available on a commercial consultancy basis to clients with the UK, and internationally. The Authority also now licenses its unique mining hazard data-sets commercially to major infrastructure operators, for hydrocarbon exploration and to value-added re-sellers, and is expanding its range of information services.

Through the success of this strategy the Authority looks forward to carrying on its essential work in protecting the public, property and environment from the legacy impacts of mining.

Further information

* The Coal Authority, 200 Lichfield Lane, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire NG18 4RG. Steven Kershaw is now retired.