He attributed much of his outcrop-style mapping – now universally adopted - to Annie’s advice. He felt that outcrop shapes should be sympathetic to the topography – “feel the curves” – and insisted that “a map must be beautiful”.

During the First World War (he was exempted from military service) he had a permit to work along the guarded coast - but was once arrested when observed working in a deep gully. Although soon released he was set upon by an angry mob believing him to be a spy and was saved by a policeman who escorted him to the railway station.

As Greenly moved away from the simpler rocks of the Carboniferous and Ordovician he had to face the complexities of the glaucophane schists, gneisses and the Coedana granite in the centre of the island. Eventually he also had to confront the schists and quartzites of Holy Island, which he viewed with “great trepidation”. Clough visited him in 1907 and suggested that there might be repetition by nappe-like isoclinal folds within these rocks, a concept that was becoming clear in the Alps and which Clough was developing in the Dalradian. Greenly readily adopted this idea although it was later proved incorrect by Shackleton (1957) on the basis of sedimentary structures; although Greenly was aware of cross-bedding and graded bedding he would not have expected them in these older schists and quartzites.

However, Greenly became aware of the presence of the magnificent, large-scale, upright folds in these rocks when he drew the coastal section, during a perilous journey in a steam life-boat. It is clear from his beautiful drawings in the Memoir that he was also aware of the relationship of minor to major folds, and of the consistency of axial plunge of the various scales of folds. Moreover he clearly appreciated what we now call ‘refolding’ on various scales.

Greenly received many geological visitors, especially Barrow, Clough, Dakyns, Lamplugh, Horne, Kilroe and Matley. Barrow stayed for two weeks and gave great help with the schists and gneisses. He became great friends with Blake and Calloway, despite their opposing views about the Moine.

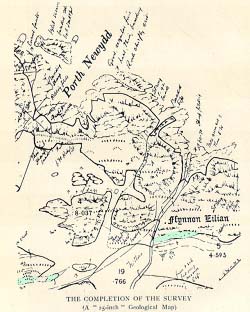

Annie Greenly was a frequent spectator, often sitting on hilltops while her husband mapped, and acted as his look-out for express trains in railway cuttings. Transport around the island, which has an intricate network of minor roads (then unpaved), was by foot, bicycle and train. Their home was a cottage that the couple had built within easy reach of Bangor station. For remoter areas Greenly took ‘country quarters’ which, as work progressed, meant being away from home for most of the year. Otherwise, Annie would go ahead by rail to find quarters in cottages, inns and farms. Annie visited Edward at weekends, bringing home-made food, often walking five miles from the nearest station. She made him send her ‘quarterly returns’, just as he would have done in the Survey, giving the linear miles of boundaries and the square miles mapped. The square mileage was often not more than 20, but his boundary mileage to the square mile was often as much as 30. It is worth noting that Greenly was one of the first geologists to outline exposures precisely on his maps.

The mapping was completed after “15 years, 4 months and a fortnight” on 8 October 1910, on a remote hillside in the north of the island. He shut his map-case and embraced Annie, who was by his side. In 1920 the 1:63,360 map, delayed by the Great War, was published together with its detailed two-volume Memoir. In 1927 Annie, aged 75, died at home in his arms. Greenly later donated money to the Geological Society of London for the Annie Greenly Fund, awarded to this day for detailed geological mapping.